Remember VIPER, NASA’s Off-Again, On-Again Lunar Rover? It’s Still in Limbo

NASA’s nearly complete yet canceled lunar rover VIPER isn’t going to get carried to the moon by a private space exploration company—but it’s also not quite dead yet

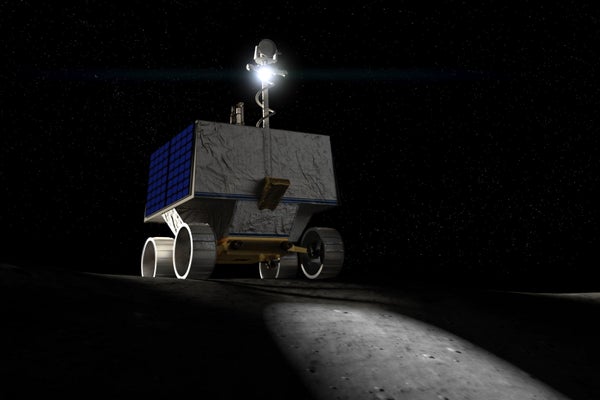

NASA’s VIPER, or the Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover, can be seen in this artist’s impression.

The only consistent thing about NASA’s VIPER lunar rover is that the road to the moon has been a rocky one. And now the space agency has nixed its attempt to find a commercial partner to launch VIPER moonward, leaving the nearly complete little space vehicle in a continued state of limbo.

VIPER (Volatiles Investigating Polar Explorer Rover) was intended to launch this year to explore the lunar south pole in search of buried ice and other chemical compounds. But NASA canceled it in July 2024 after delays led to cost overruns. This is the second time NASA has nixed a lunar rover mission in recent years, says Philip Metzger, a planetary physicist at the University of Central Florida (UCF). In 2018 NASA axed the Resource Prospector rover, which would have done similar exploration.

In January NASA raised hopes that VIPER might somehow still see space when it put out a call for proposals for private aerospace companies to launch and operate the rover. On May 7, however, NASA canceled that call for proposals.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The agency says it is exploring new strategies for VIPER in the future.

“We look forward to accomplishing future volatiles science with VIPER as we continue NASA’s Moon to Mars exploration efforts,” said Nicky Fox, associate administrator of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, in a recent statement.

Why can’t VIPER get off the ground?

The rover’s budget problems started with supply chain disruptions during the COVID pandemic, says Casey Dreier, chief of space policy at the Planetary Society. It was also slated to launch on a platform built by aerospace company Astrobotic, which failed its first landing of a scaled-down version of that platform

The mission was unusually far along when NASA pulled the plug: the rover was fully assembled and was in the final stages of testing for a launch. By that point, NASA had sunk nearly $800 million into its construction and the contract with Astrobotic.

It’s not clear why NASA has been unable to find a private partner to launch the rover, but such a company would have assumed the costs of the mission and agreed to share the data freely with the space agency. That made for a tough business case for private companies, SpaceNews reported earlier this month.

What kind of science was VIPER supposed to do?

The 2.5-meter-tall rover was designed to search for resources such as water ice, carbon dioxide and helium in the lunar subsurface. The goal, says Clive Neal, a lunar expert at the University of Notre Dame, is to find resources that humans could use to establish a permanent research base on the moon. The data on where such volatiles might be and whether they’re accessible and extractable are crucial for the Artemis program’s plans for long-term human presence on the moon.

The rover carries four instruments: a neutron spectrometer to detect water as deep as a meter below the surface, a near-infrared spectrometer to determine the makeup of samples, a mass spectrometer to analyze gases in the environment at touchdown and a drill called TRIDENT (The Regolith and Ice Drill for Exploring New Terrains). The drill is one of VIPER’s blockbuster features, designed to pull samples from up to a meter deep.

The cancelation of VIPER, after 2018’s loss of Resource Prospector, is short-sighted, given NASA’s goals, Neal says. “Is NASA actually serious about getting humans back to the moon?” he says. “Are they actually serious about enacting our current space policy? Have they actually read it?”

VIPER could also answer basic science questions about the origin of the water on the moon, says UCF’s Metzger. It may have been part of the lunar core from the moment of its formation, or the water could have arrived with planetary dust or large impactors over time, among other possibilities. “Understanding those processes is crucial for understanding our solar system,” Metzger says. The answers could reveal more about how common water-rich bodies are in the galaxy and how many planets or moons might host life.

What’s next for VIPER?

That’s the big question. Until NASA releases more details on potential future partnership structures, the project remains in a state of suspended animation.

“I don’t know what to make of it because there is so little information,” Dreier says.

It’s possible NASA could reopen negotiations with Astrobotic, the company that was originally going to launch the rover, Neal says. Or, Metzger suggests, the agency might be seeking international partners that could take on some of the operational costs.

There are no other U.S. missions on the horizon with the drilling capabilities of VIPER. If the rover doesn’t find a way to the moon, Neal says, two other lunar explorers from China could pick up the banner of volatiles science: Chang’e 7 and 8.

As uncertain as things are looking for VIPER, though, it’s an optimistic sign that NASA hasn’t dropped the rover outright, Dreier says, given that the White House has proposed a 50 percent cut to NASA’s science programs and a more than 20 percent cut to the agency overall in 2026. “If it’s not openly identified as being canceled,” Dreier says, “you are winning as a NASA science mission right now.”