At Y Combinator’s Little Tech Competition Summit in downtown DC last week, there was an air of optimism and something verging on camaraderie among a surprising crowd. Sen. Cory Booker (D-NJ) — barely recovered from his 25-hour speech about preserving democracy on the Senate floor a day earlier — showed up to discuss the importance of competitive tech markets. Sen. Josh Hawley (R-MO), a staunch ally of President Donald Trump and longtime Big Tech critic, struck similar notes. Lina Khan, former Federal Trade Commission chair during the Biden administration, posed for a photo next to former Trump adviser Steve Bannon, who has openly praised her work.

About half a mile away, at the American Bar Association’s annual spring antitrust meeting, the mood was less triumphant. In the Khan era, the meeting served as a place for antitrust defense attorneys to grumble about President Joe Biden’s tough merger and antitrust policies. This year, the familiar policy conflicts were shot through with a sense of foreboding over Trump’s gutting of regulatory agencies and attacks on the legal profession itself.

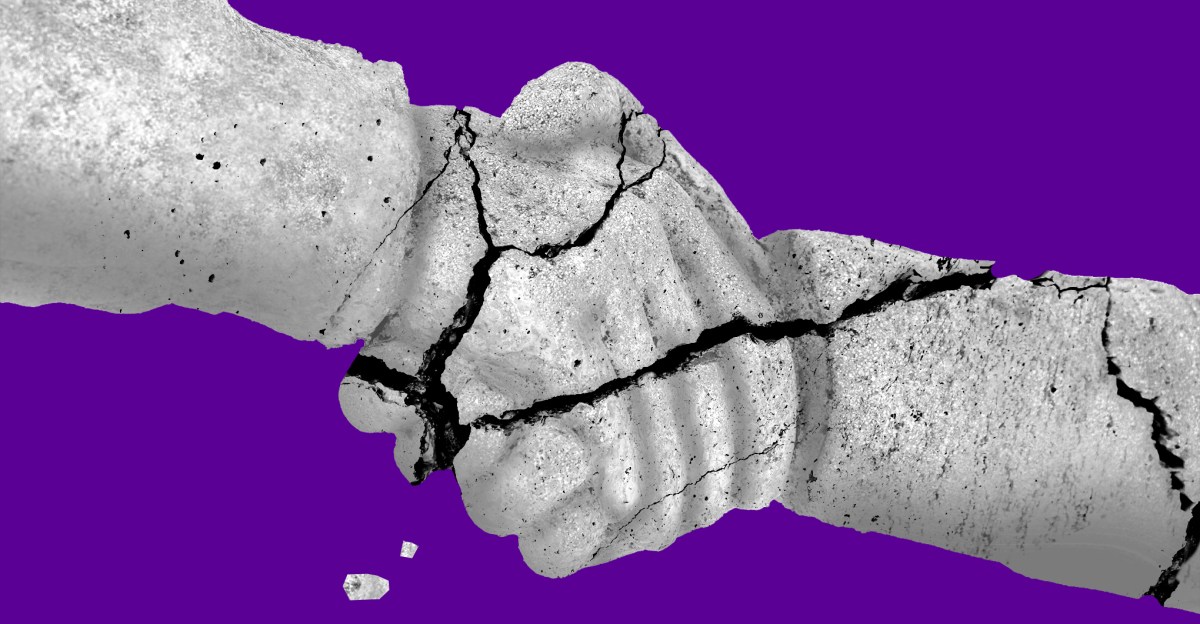

Inside the airy, light-filled room, many speakers at the Little Tech Summit appeared in lockstep on the idea that tech giants had been allowed to run amok and finally — finally — a populist movement to change that has taken hold. For a few hours, the kind of bipartisanship that’s often spoken about with nostalgia appeared to be very much in the present. But beneath the surface lay tensions about whether Trump’s dismantling of administrative agencies was undercutting a robust antitrust agenda, and whether bipartisan consensus could survive Big Tech’s newfound friendliness with the right.

“If you want to govern in ways that checks the power of Big Tech or other monopolists, you need a government”

Khan may be smiling in her photo next to Bannon, and at the summit, both she and her Republican successor Andrew Ferguson sounded similar alarms about monopolized tech markets. But the conference came just weeks after Trump attempted to fire two Democratic colleagues — a move Ferguson sees as perfectly fine.

After appearing on stage, Khan denounced the firings to reporters, calling them a blow to the very causes Ferguson says he supports. “If you want to govern in ways that checks the power of Big Tech or other monopolists, you need a government,” she said. “And if you are simultaneously trying to dismantle the government or weaken it, or take apart the administrative state, there’s a real tension between that project and wanting to take on monopolies. And so, I do think this is a basic tension in the Republican project.”

Khan raised a question that represents the tenuousness of the alliance between progressives and populist conservatives: are her allies in the Republican Party, particularly the Trump administration, actually committed to the cause? “It’s very easy to kind of talk about how you want to be tough with monopolies, but when push comes to shove, are you actually going to take action?” she asked.

The “basic tension” Khan mentioned has been heightened by increasing collaboration between Trump and Silicon Valley. Ferguson spoke on stage of an aggressive approach to Big Tech, but when asked afterward about how he’d handle Trump ordering him to drop a case like the upcoming antitrust battle against Meta, he said he doubted Trump would do such a thing, but that it’s ultimately important he “obey lawful orders.” Soon after, a CNN reporter posted that Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg was seen in the West Wing, and The Wall Street Journal later reported he was there to try and talk his way out of the antitrust trial that begins on April 14th.

The Little Tech Summit was clearly the hot antitrust ticket of the week in Washington. At the ABA meeting, held at the Marriott Marquis, well-dressed lawyers milled about wood-paneled rooms with abstract blue and beige carpets. Skeptical antitrust attorneys would typically pack the hotel’s large ballroom to see the top US federal enforcers speak, but Ferguson and his Justice Department counterpart Gail Slater had broken with tradition and declined to participate. Ferguson published a letter that accused the ABA of having a “long history of leftist advocacy” and attacking “the Trump-Vance Administration’s governing agenda.” That left this year’s enforcers roundtable — usually a keystone event of the conference — relatively sparsely attended, featuring enforcers from Europe and South America but none from the US.

Even as lawyers seemed hopeful about a future of more dealmaking and relaxed regulation under Trump, some speakers sounded the alarm about the same issues as Khan. A fairly popular panel featured Rebecca Slaughter, one of the two commissioners Trump removed. Slaughter received rounds of applause from attendees when she spoke about standing up for democratic principles — a reception she acknowledged was unusually friendly.

“I don’t think this is an antitrust ideology question. I think it’s sort of an institutions of government, rule of law question”

“I have always come to this event, even though most of the people here don’t particularly agree with me about most of my legal views, because I think it’s important to talk to people who don’t agree with you,” Slaughter said. “It is very encouraging to hear support, including from people who don’t always agree with me, because I don’t think this is an antitrust ideology question. I think it’s sort of an institutions of government, rule of law question. And that should be an area where we can find a lot of common ground.”

At times, sitting several stories beneath ground level under artificial light, one could easily forget the upheaval Trump has exercised across the government. At a panel about the past, present, and future of the FTC, former commissioners of different parties waxed poetic about the historical bipartisanship of the agency.

But even there, former Democratic FTC commissioner Terrell McSweeny threw cold water on the discussion. “You guys are dancing around the thing that I think we really need to talk about,” McSweeny said around 45 minutes in. She brought up the “Humphrey’s Executor elephant in the room” — referring to the long-standing Supreme Court precedent barring the president from firing a commissioner without cause, which Trump’s firings openly violated. “What do you all make of the moment we’re in,” she asked, where once-independent agencies were being “reoriented” toward enacting the will of the White House?

The two Republicans on the panel, former acting chair Maureen Ohlhausen and former commissioner Noah Joshua Phillips, appeared mostly unconcerned — questioning whether the Supreme Court precedent was still relevant and whether barring a president from firing a commissioner is really the true marker of independence. “We have agencies in the US government that operate with a great deal of independence without that,” Phillips said.

After the panel, McSweeny reflected on the coalition of progressive Democrats and “new right” Republicans who’ve converged on antitrust. “It’s maybe a natural evolution of some of the debates that have been happening. But I think it’s still relatively new,” she said. Will Trump’s dismantling of the government shake that tenuous allyship? She answered quickly: “I think we don’t know yet.”