Before it occurred, the drama on the Piccadilly Line, I was one of those people employed to clean up the radio archives at the BBC. I’d written a book called Muriel Spark and the Comedy of Fact and was still smarting from the silence surrounding its publication. People talk such garbage about failure. They say it’s the attempt that counts, that failure is a great teacher. All I know is that success improves your life, and when it doesn’t come you’re left with a sense of premeditated injury. I joined a part-time MA in journalism at City University, where some of the students had tattoos, nose rings and pale blue hair. We yearned to report on the inner reaches of ourselves. All data was of course credit data. All reporting was surveillance. In good journalism you get to see what happened, but in the best you also get to see what might have happened instead.

‘You guys want to believe that stories belong to the people they’re about,’ the professor said one cold evening in the lecture hall, ‘but that’s just not true. History is merely a chronology of accidents and journalism a perpetual clean-up operation.’ His accent was strong. Welsh. The hall smelled of damp wool. The students seemed super-alert. Outside the window, the lights of Clerkenwell glowed through the rain.

‘I don’t think so,’ the young woman sitting in front of me said. Professor Madoc behaved as if all opposition was enjoyable. You had the impression he kept his deepest professional experiences to himself, and that he doubted your capacity for reality. I admired him, perhaps more than I should have. I like the idea that minds improve by confronting difficulty, not by meeting reassurance.

‘Look out for that form of sentimentality known as privacy,’ he said to the hall. ‘It’s redundant. Your job, your only job, is to expose the truth, with no regard for special interests, the special interests of corporations as much as individuals.’

‘I’m not sure that’s right,’ I said, with my hand up (an old habit). ‘Surely it’s not okay to harm or offend people just to get information?’

He came straight back at me. ‘Offence is merely a by-product of good reporting,’ he said. ‘People’s feelings are irrelevant.’

‘That’s over the top,’ I said to the students rather than to him.

‘Speak up!’ he shouted. ‘I can take it.’

‘That’s really questionable,’ I said, a little louder. ‘You’re making it sound like reporting is a form of exploitation.’

‘You’re saying you can’t cope with it?’

‘You’re framing the whole thing as an immoral act.’

I couldn’t tell if the other students knew that Madoc and I had become friendly. I was a little older and already hired by a corporation, which may have annoyed them. He had a tendency to pick me out. Over drinks, he had told me I should be thinking about long-form. I suppose most of them imagined we were just two blokes in a competition to mansplain, but Madoc could be insightful. I thought he could help me.

‘In a time when all information is gathered and controlled by potentially bad actors,’ he said, ‘we can still believe in the power of the individual witness to circumvent that control. I don’t know if you believe that, Mr McAllister. You’re from the United States, no?’

‘I won’t deny it,’ I said, putting down my pencil. ‘Philadelphia.’

‘Home of The Philadelphia Inquirer. Well, people either believe in journalism or they don’t, Michael. They either like the truth, or they hate it. Some of you want to be activists, yet you’re frightened of offending anyone. But, let me tell you: objectivity takes a degree of courage, and this business is not a niceness contest. It’s brutal. It should be brutal.’ I think the students were put off by his categorical way of speaking. Some of them looked at me, as if I might know how to make him less like that.

There was a loner-guy in the second row. That evening, he seemed especially agitated, pulling his headphones on and off, the music suddenly blaring from his cans while Madoc continued to speak. There’s nothing more insistent than other people’s music. It was a jagged sound, thrash metal or whatever, and its discordance began to feed an anxiety already there in the room. ‘Fucking bullshit!’ the guy shouted, pushing the headphones back on.

‘I think you should leave the hall,’ Madoc said.

‘Like you know anything.’

‘Just leave.’

The guy provoked confrontation yet seemed to hate the attention. I’d often see him craning round to look at me during the class. A week on, it must have been him that stuck a Post-it note on the bench where I sat. I found it when I came in and could see the back of his head, nodding with his cans on. Then he laid his head on his folded arms for the whole hour. ‘SPEAK UP!’ the note said.

I’d come to Broadcasting House after two years at HarperCollins as a sensitivity reader. By my count, I’d saved twenty-six authors from making jerks of themselves or being cancelled, and now I was in this open-plan office on the fourth floor, trying to sort out the archives of Desert Island Discs. Archive cleansing was hardly my life’s ambition – a frontline assignment was the aim, or a serial podcast – but they allowed me to work flexible hours, and it calmed the mind to be assessing old recordings and listening to the variously intelligent and prejudiced questions of Roy Plomley and Sue Lawley.

‘What’ve we got?’ my boss Lillian asked me one morning, as she peeled a banana by my desk.

‘Well, there’s the interview with Ian Fleming from 1963 –’

‘What’s wrong with it?’

I looked down at the notes in my iPhone. My habit was to listen everywhere, at the shaving mirror, in bed at night, jogging at Fitness First, and the stuff I noted was relevant and to the point.

‘The way he describes the sex life of James Bond. Might sound a bit rapey.’

‘Oh, really?’

‘The problem’s the presenter. He says how lucky it was for 007 to be meeting “these lovely and cooperative girls”.’

‘Oh dear.’

‘Like, can we even say “cooperative”?’

Lillian went to the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary.

‘It suggests a certain amount of coercion,’ I continued.

She found the page. ‘Working together, acting jointly,’ she said, looking up. ‘It says “willing”.’

I told her I thought it would be safer to cut the question. The archives were full of holes and omissions – missing tracks, speech breaking off, material lost or damaged. Deletions in the recordings were unlikely to be noticed.

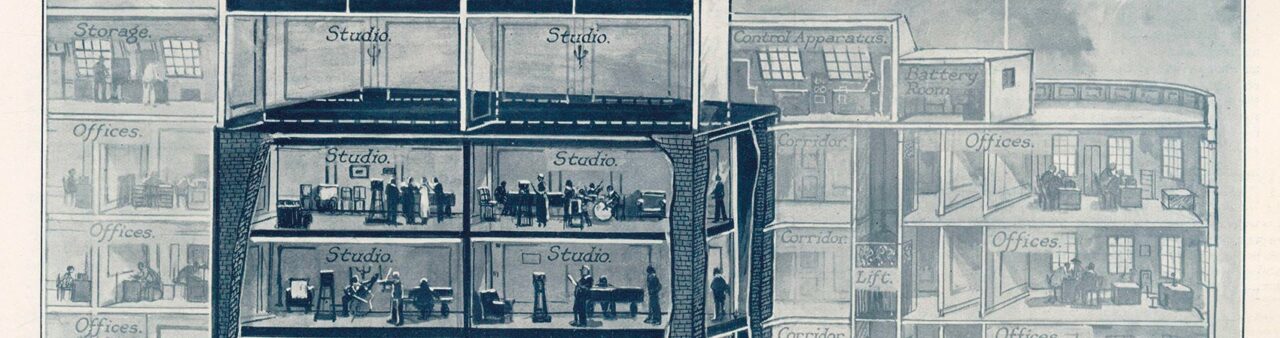

Broadcasting House is filled with old sound. When I walked the corridors and peered into the empty studios, there was always something of a distinguished echo, a combination of past laughter and bulletins. Maybe the cue lights on the green baize offered a sense of occasion. Nostalgia. The air in all those rooms and in the entire building was tense with spoken things, as if what had been said on the airwaves still lingered in particles and spores. That’s how it struck me anyhow. You think you can hear Orwell and the 1930s poets, and there remains in the elevator lobbies the smell of shoe polish and stewed tea.

Our section – the Department of Misspeaking, as our waggish colleague Nicholas Winslow-Brown called it – was one of the newer ones sprouting up all over the place. Lillian used to work on the Today programme, and she had been seconded to us, aged sixty-four. She had incredible news sense and you had to admire her experience. Nick was an archivist of sorts. He cycled in from South Norwood three days a week. His life’s passion, if that’s not too strong a word, was British comedians of the 1970s. He never found anything offensive: all subjects were good for a laugh. He collected old recording equipment and could bore you out of your mind when talking about radio frequencies. He was the God of Easy Listening, but his lightness made us grave.

‘Okay. What else?’ Lillian asked me.

‘I’m not sure it’s cool that Joseph Cotten says he once kicked Hedda Hopper in the ass. Random violence towards women. And . . .’

I scrolled down my list of notes.

‘Victoria Wood introducing a track by the Weather Girls? She describes them as “two enormous black women”?’

‘Yes, cut that.’

‘And the novelist Beryl Bainbridge saying women can never be equal to men.’

‘She was eccentric,’ Lillian remarked. ‘Nobody could take that seriously.’

‘It’s up to you.’

‘I understand the task, Michael,’ she said.

Lillian was inconsistent. She wanted the Corporation to meet improved standards, but she wasn’t persuaded by my own efforts. She said I had the brain of a single man and that I reasoned like somebody who didn’t have kids. She wasn’t wrong but her remarks were inappropriate, I thought.

‘There’s an interview here from 1968,’ I said, ‘with Louis Armstrong. Fairly upsetting.’

‘I’m really not keen to cut a contributor of colour,’ Lillian told me. ‘We have too few, especially from those years.’

‘Of course,’ I said, swiping to get to the offending section.

‘You’re about half the size you were when I last saw you,’ the interviewer was saying. ‘I’ve been getting too much to eat,’ Armstrong replied, ‘but I’ve learned the psychology of leaving it all behind me every morning. You understand?’

Lillian was nodding. The interview continued.

‘You don’t need it after the taste is gone,’ Armstrong added.

I stopped the recording and scanned Lillian’s exhausted face. ‘That sounds like an advertisement for bulimia,’ I said.

Two weeks later, the thing started. I was perched at the counter of a sushi place in Regent Street, when suddenly I got the feeling I was being watched. When I looked up from my tray, there he was – the loner-guy from City. I’d like to say his presence was unexpected, but somehow it wasn’t. He sat down on the stool next to me, licking a cigarette paper and blinking crazily. I say crazily: I don’t mean to judge him, but he absolutely seemed like he had mental-health problems. When he spoke, it became clear that he had this little fund of second-hand knowledge; he knew, for instance, that Professor Madoc was married with kids, and he knew about my work with the BBC, casually dropping it into the conversation as if gathering such information was a hobby of his.

‘How do you know that?’ I asked.

‘It’s on your Instagram bio, dude,’ he replied. ‘It’s not rocket science. You were a sensitivity boffin for a major publishing house.’

He spoke about ‘testing reality’ and ‘making things happen’. When he lit the cigarette he’d been rolling, the manager came over and asked him to leave. Pointing at me, the student said it was stupid to trust pilots from countries where they believe in the afterlife. ‘I’m telling you, brother,’ he said, ‘when it comes to pilots, you’re much safer when they don’t.’

The manager started jostling him. ‘Let’s move,’ he said.

‘People’s minds, man,’ the student said. ‘You never really know what’s going on in there, do you?’

That afternoon, Lillian wanted to go over some of the fixes. Winslow-Brown was with us, serving as comedy’s great advocate. Her desk overlooked All Souls Church on Langham Place, with Regent Street beyond. ‘The word has come down,’ she said. ‘We need to incline more towards Michael’s approach.’

Nick cocked his head and smiled. ‘Expunge all the bad attitudes?’

‘I don’t like it either,’ Lillian said. ‘Desert Island Crimes. The Big Bigots Conventicle. I feel like we’re rubbing out history, all in the name of –’

‘Social awareness?’ I offered.

Nick sniggered into his travel mug of coffee.

Lillian tapped a pencil on the edge of her desk. ‘Well done,’ she said. ‘Management is happy with what we’re doing. I don’t pass all your suggestions up the line. I tend to agree with Nick, that human nature is not improved by concealment, especially when it comes to the past. But management wants a bit more . . . Em, attentiveness. Your latest points . . .’

She touched her laptop and read aloud. ‘. . . Sondheim is belligerent, defensive, immodest.’

‘And that’s now considered out of order, is it?’ Nick asked. ‘That’s now banned, a person demonstrating his character?’

‘It would appear so,’ Lillian said.

I tried to adopt a more junior tone. ‘Guys. You employ me to listen and tell you what I think. My notes are only suggestions.’

Lillian flicked her trackpad. ‘Yes. I listened last night to a few of the latest things you flagged. Natalie Wood speaking in a faux Mexican accent. “You dirty gringos, et cetera”. She’s having a bit of a joke, no?’

‘Possibly,’ I said. ‘But 150 million Mexicans aren’t laughing.’

She nodded, reading on. ‘The travel writer Wilfred Thesiger. He talks about areas of Arabia being “pacified”. He shot lions in the Sudan.’

‘I’ve heard that one,’ Nick said, his bottom lip out. ‘Isn’t it all about sweet-smelling roses at the edge of the desert, the beauty of shifting sands?’

‘That’s not the worrying part,’ I said. ‘We don’t punish clichés.’

‘He’s a type,’ Lillian said, staring at her screen. ‘We can’t uninvent him.’

‘It’s just over, I guess.’ I was trying not to sound irked. ‘A white man, schooled at Eton, trying to be funny about the dance moves of Ethiopians. I don’t know how harmful it is, but I can tell you it’s offensive.’

‘Rex Harrison,’ she continued, ‘ticked off for blacking up in a play by Eugene O’Neill.’

‘Not for doing it,’ I said, ‘that’s none of our business. For talking about it light-heartedly on a programme we are making available for rebroadcast.’

‘Quite so,’ she said, with a tight smile. Lillian seemed to hate her job and blamed me for helping her to do it properly.

‘Roald Dahl, of course. Everybody’s taking great chunks out of Roald Dahl.’

‘For fuck’s sake!’ Nick said. ‘He was an entertainer.’

‘And so were the Black and White Minstrels,’ I said, ‘but you’re not proposing to stream them all over the place, are you?’

My father used to say the important stuff happens when you’re looking the other way. You’re fast asleep or busy worrying about the car insurance or what to cook for dinner. I’m not sure I can agree with him. I trained myself early on to recognise big events, and keep my own preferences out of the picture. News is like that: it’s other people, most of the time, though I increasingly fear that everything’s subjective. I mean, you arrange your perspective according to who you think you are.

In the late 1980s, my father learned his people were related to the abolitionist who owned the McAllister farm south-east of Gettysburg. He visited the US from Scotland in search of his American roots, and he met my mother in Philadelphia. They went to work for The Inquirer. He left us on my sixteenth birthday. He returned to the UK and to a sort of oblivion. When I was in my senior year at Yale, I received a letter in which he said there were too many things he didn’t get right. ‘Your mother deserved better than me,’ he wrote, ‘but I just couldn’t make it and I’m sorry about that.’ When he died, his second wife sent me a freezer bag containing a tartan scarf and a harmonica. ‘I thought you might like these,’ her note said. ‘Your father was always sad not to have known you better.’

I left Broadcasting House at three o’clock that day and walked down to St James’s Square, where I sat on a bench under the plane trees, making notes on an episode from 1979. ‘Is it okay for the playwright Peter Shaffer to talk about possessing the spiritual essence of the Inca?’ I walked over to Haymarket to get coffee and was aware of eyes at a certain point: a familiar person passing by, then a clear view of him, the guy from class. It was like he wanted to look at me or say something, and I was confused by it and sort of spaced out. If you’re built for it, all attention is a sort of aphrodisiac. He disappeared again and it was close to five when I got to the underground station. A guitarist was playing in the tunnel and the music echoed. On the crowded platform, I heard the shots. People ran and screamed. I took out my phone.

‘Oh my God! He’s going to shoot people!’

I remember a woman yelling that. A train came in on the other platform and everyone rushed towards it as I saw him firing at the ceiling.

I was already filming when he walked towards me. It was as if the commotion was soothing to him. One of the Transport for London workers was shouting into a digital loud hailer. ‘All passengers please clear the platform!’

The student turned to me, stepping closer.

‘I’ll record it for you,’ I said. ‘Don’t shoot.’

‘It’s hard to work out the maths and the physics,’ he said casually. ‘The acoustics, I mean. Trying to figure out what’s right.’

There was a pinkness to his eyes. He wore a backpack and jerked the gun in the direction of the steps.

‘Just science,’ he said.

I stared at him. My hand was shaking. He was careful in the way he reached into his backpack – he had fingerless, mesh gloves – and put what I think was another cartridge into the gun and hammered it in with his palm.

‘Keep your camera on,’ he said.

My eyes tried to focus, and the place seemed emptier. I can remember the posters behind him and the noise of an alarm going off.

‘Stop this,’ I said. It came out as a whisper.

He seemed exhausted. He seemed like he’d overthought everything. I remember how he let his firing arm flop down to his side. He walked closer and I thought I was finished, but all he did was hand me a plastic key card.

‘Room 204. Premier Inn. Heathrow. Terminal 3,’ he said.

I put the card immediately into my pocket. There was a sound of radio crackles, and I could see a number of people coming up

behind him.

‘Thank you,’ he said. ‘Sometimes you need help.’

I lifted the phone with a sense of purpose, using my thumb and forefinger to zoom in on his face. He looked sensitively into the camera before raising the gun again, at which point he was pulled by several people to the ground.

They’ve had a bunch of war reporters on Desert Island Discs. The photojournalist Don McCullin was one, interviewed in 1984. He spoke of being in Beirut a year earlier trying to photograph a woman. ‘She was very cross, and she punched me,’ he said. The woman then went round the corner and was killed by a car bomb. ‘I wished the woman would have punched me ten times as hard,’ he said, ‘to somehow exonerate my misjudgement that day.’ A lot of the other reporters who came on the show are now forgotten, people like Godfrey Talbot, a broadcaster who had been embedded with allied troops at El Alamein and Cassino. ‘I don’t know of any assignment that is so rugged as a major royal tour,’ he said, with what I take to be a 1950s sense of proportion.

Nobody was hurt that day at Piccadilly Circus. The young guy was arrested. I don’t know what to say about randomness or predestination or whatever. When they took him away, a female officer asked if I was okay, and I nodded. They would check the CCTV, I supposed, and have more questions later. The station was closed and cordoned off, so I couldn’t take the Tube to my destination. It was dark when I emerged onto Piccadilly, into the blue lights. I was worried the police might come at any moment and take my phone away for analysis. I emailed the footage to Madoc, and hailed a cab on Haymarket, feeling the guy’s key card in my pocket.

I had reached Hammersmith when Madoc called.

‘Are you okay?’ he asked. ‘You were right there, man. That’s the nutter from our class.’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘I saw everything.’

‘That’s insane. Was he trying to . . . ?’

There was nothing to say to him. It was all on the recording. What the guy did and what he didn’t do and what he might have done. The police later found him on CCTV footage from weeks before, asking the security guard at Broadcasting House how to get work in the media. He posted screeds about our course on Reddit. The police would say he’d sent me an email after reading my first published article in Prospect, but I never saw it. They now say he was a fitness fanatic who had spent months trying to buy a firearm. He’d put a message about me in a BBC suggestions box. ‘The guy wants to be a reporter,’ it said, ‘and he needs a story.’

‘There’s obviously something wrong with him,’ Madoc said that night, ‘but I didn’t think he was capable of anything like this. Where are you now?’

I didn’t tell him. He asked me what I wanted to do with the video. I wasn’t sure. ‘I know a producer at CNN here in London,’ he said. ‘They’ll pay you for it, but they’ll want to interview you as well.’

Passing over the Hammersmith Flyover, we encountered roadworks. They drowned out most of what Madoc was saying. I told him to take care of the footage. He should do whatever he thought was right.

He was waiting for me to say something else. ‘Do you want me to come and get you?’

‘I’m good,’ I said.

‘We just don’t know what’s in people’s minds.’

I think that’s what he said. That’s what the guy had said, too.

Unless you happen to enjoy the journey to a journey, the airport run feels like the first link in a chain of dislocation. The short-term parking, the shuttle between terminals, the say-hello-wave-goodbye routine of coffee bars and trinket shops: it makes you wonder if you were ever on solid ground. Going down the M4 feels austere. I think of those highways as among the final staging posts of royal funerals, where the mourners line the route as the cortège makes its way from the historic centre to the resting place.

Terminal 3 had an atmosphere of purpose. Maybe it was the drag of wheelie-suitcases over wet gravel. The smokers outside the building looked like they were going everywhere and nowhere at the same time. Piccadilly already seemed like an urban myth. The cab had dropped me off at the terminal building, so I walked past multi-storey car parks to find the hotel. When I reached it, the Premier Inn felt like a place I’d been getting to know all my life.

I knew I had to reach the room before the police got wind of it and turned up to investigate. I went straight past reception and up in the elevator to the second floor. At 204, a ‘Do Not Disturb’ sign hung on the door handle; the lock was released with a knowing click. Inside: drawn curtains. The bedside lights were on, and the bed looked as if it hadn’t been slept in, but there was an impression on the white duvet, just about my length and with a dent in the pillow. I found a pair of AirPods in the bathroom and put them in my pocket. A computer charger was plugged into the wall and a neat pile of books sat on the desk. Open by itself was a copy of my own book, held flat by a mug of cold tea.

Image © Alamy, Diagram by G.H. Davis showing the new Broadcasting House in Portland Street, London, 1931