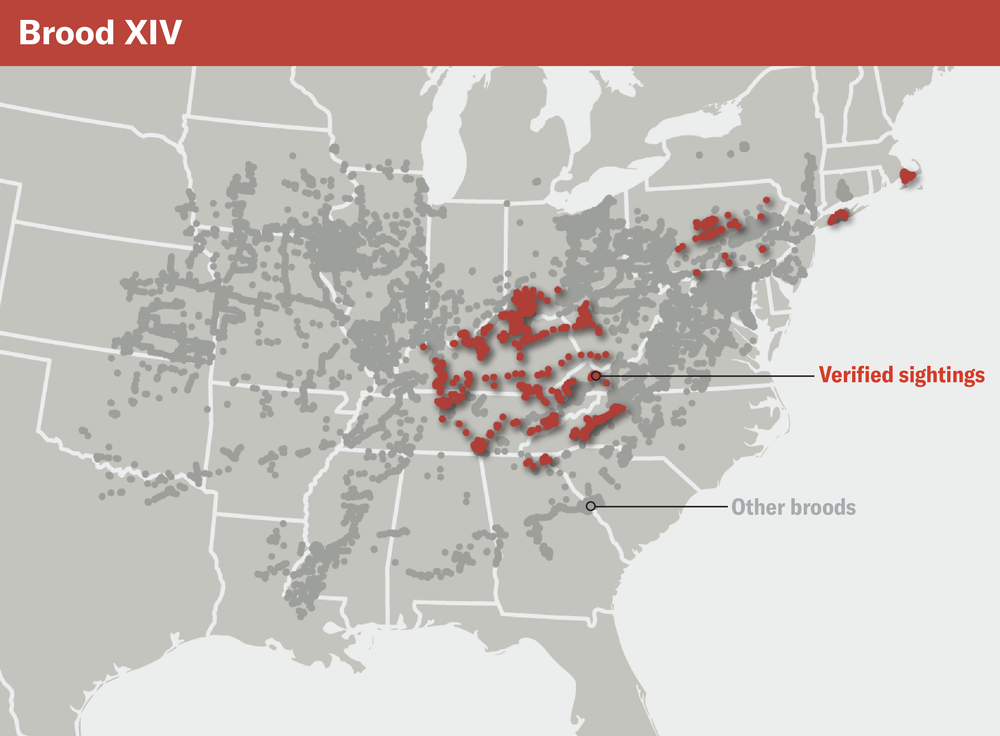

As spring warms the eastern U.S. and green shoots peek from the ground, other forms of life stir in the soil. Periodical 17-year cicadas in Brood XIV—one of 15 broods found only in North America—begin to creep from their underground burrows. Last seen in 2008, they will emerge in the billions across a dozen states from early May through June.

Above ground, flightless cicada nymphs transform into black-bodied, winged adults, ready for a month-long bacchanal of song and sex. But for many cicadas—possibly tens of millions—mating will be a gruesome parody of procreation in which their body is turned into a disintegrating puppet by the deadly fungus Massospora cicadina, which only infects 13-year and 17-year cicadas.

An infected insect will try to mate even though its genitals have been consumed by the fungus and replaced by a plug of fungal structures called conidiospores, which spread their “zombification” effect on contact. M. cicadina makes male cicadas flick their wings like amorous females do; healthy males become infected when they try to mate with the imposters. The fungus also floods cicadas with cathinone, a stimulant that also occurs in khat, a plant chewed as a recreational drug in some parts of the world. In cicadas, cathinone may boost hypersexualized behavior.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“It’s sex, drugs and zombies,” says John Cooley, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Connecticut. “Nature is stranger than any science fiction that’s ever been written.”

Massospora cicadina-infected 13-year cicadas (Magicicada tredecassini) collected in Nashville, Tennessee in spring 2024.

“World’s Best Study Organisms”

Fungus and cicada, zombifier and zombie: their relationship is at least 100 million years old, and scientists are still piecing together how it works, says Matt Kasson, a mycologist at West Virginia University. Every brood emergence helps address questions that can’t be answered in a lab, such as when the fungus invades nymphs’ bodies.

“When you’re dealing with something that spends 16.9 years underground, there’s a lot of uncertainty there,” Kasson says.

When M. cicadina infects adults, it produces durable, thick-walled “resting spores” that drop from its host’s crumbling abdomen onto the ground. Resting spores infect other nymphs, which, after metamorphosis, develop their own plug of stalklike conidiospores—the spores that sexually transmit the fungus to other adults. But scientists don’t know if resting spores infect nymphs after they hatch or when they surface more than a decade later.

In fact, the fungus may have more than these two spore types; they can possibly produce others that kill nymphs underground, Kasson says. Researchers recently found that M. cicadina has the largest genome in the fungus kingdom, meaning that certain aspects of its biology—such as its reproductive cycle—could be quite complex. The only other fungi with a comparable genome size are rust fungi: plant pathogens with up to five life cycle stages. Given that rust fungi and M. cicadina both have unusually large genomes, M. cicadina might share other features with rust fungi, such as multiple spore varieties, Kasson suggests.

Verified historic sightings of Brood XIV.

Daniel P. Huffman and John Cooley

According to Cooley, periodical cicadas’ unusually long nymph stage has led to a lack of specialized predators of these insects, with one exception: M. cicadina. “It’s not surprising that the thing that would crack the cicada life cycle is a fungus that can have resting stages, so it can just wait out until the appropriate time,” he says.

Because M. cicadina prevents its hosts from reproducing, the fungus may also affect cicada populations and brood distribution; that relationship, Cooley adds, is another piece of the periodical cicada puzzle.

For Cooley, periodical cicadas offer a window into species distribution and how populations shift over time. Despite their lengthy underground stage, periodical cicadas are nonetheless good research subjects because adults are abundant and easy to find.

“They’re loud; they’re obvious; they tell you exactly where they are,” Cooley says. “They turn out to be one of the world’s best study organisms for asking really big evolutionary questions about species and speciation.”

Over time, climate change and human activity have reshaped the cicadas’ habitats: populations wax and wane, and some broods vanish entirely. Brood XIV will include three periodical cicada species: Magicicada cassini, Magicicada septendecim and Magicicada septendecula. Their emergence will show how the species and populations interact and identify potential mates of their own kind.

“What I’m going after directly is the question of range change,” Cooley says. “I’m also looking for overlaps between this and other broods.” Within the broods, patterns of waxing and waning zombie infections can reveal how cicada populations change over time.

Zombie Counting and Tracking

Brood XIV cicadas will be most abundant in Kentucky and Tennessee, with smaller populations as far south as northern Georgia and as far north as Massachusetts. Places with more cicadas will almost certainly have more zombies, says entomologist Chris Alice Kratzer, author and illustrator of the field guide The Cicadas of North America.

“I would expect to see a lot more Massospora in Kentucky and Tennessee this year than in some places like Pennsylvania or Massachusetts,” Kratzer says.

Based on prior records from the crowdsourcing app iNaturalist for other broods, Kasson predicts that approximately two to four percent of Brood XIV will be zombified. For people who want to contribute to M. cicadina research, “uploading photos to community science platforms like iNaturalist is really essential for scientists like myself to figure out where the fungus is and is not,” he says.

Kratzer, who has previously confirmed sightings of cicadas and M. cicadina for iNaturalist, is also verifying Brood XIV sightings for the platform. When someone posts a sighting of a cicada with a Massospora infection, Kratzer encourages the observer to create entries for both the cicada and the fungus. “It’s a very exciting part of science to be in because anyone with a camera or a microphone can contribute.”

If cicada-spotters are patient, they could pinpoint a zombie or two. But even if they don’t find any, the sheer number of periodical cicadas is impressive to behold. With predictions of as many as 1.5 million insects per square acre in some places, this year’s Brood XIV emergence will be a sight that observers won’t soon forget.

“Everybody loves a spectacle,” Cooley says. “And if these aren’t a spectacle, I don’t know what is.”