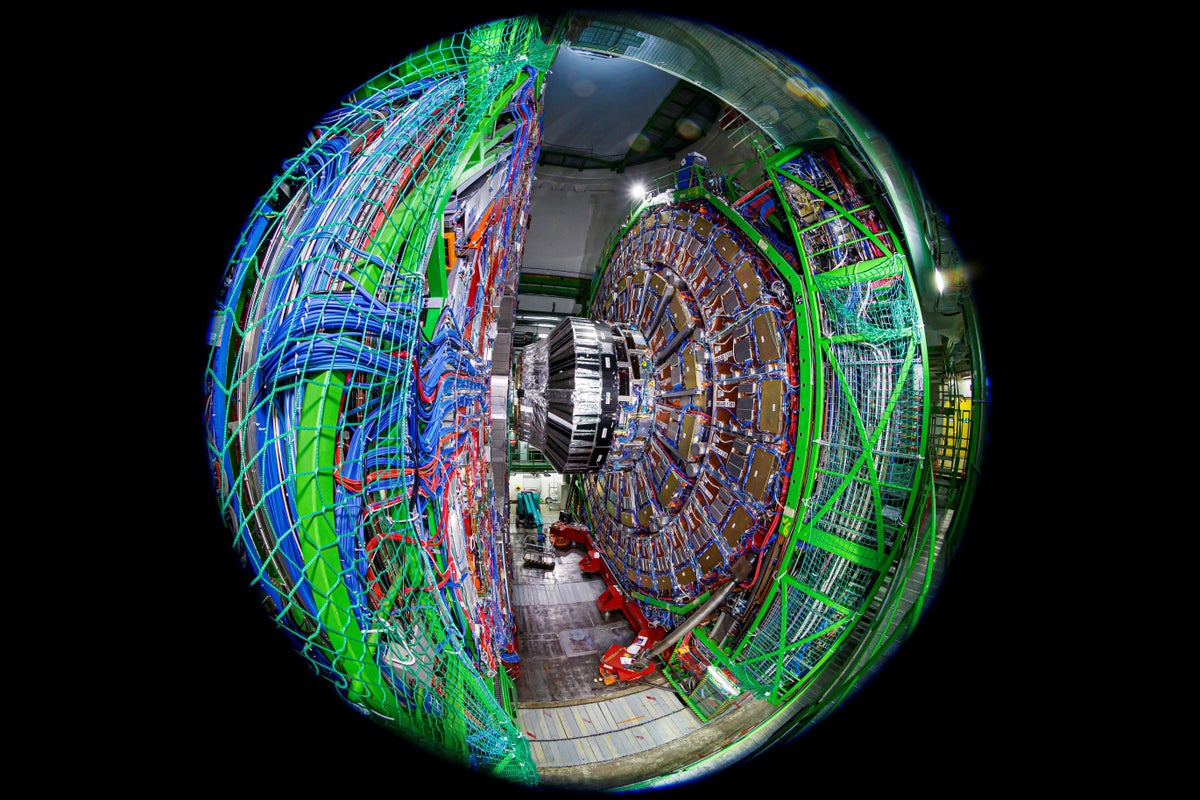

Supersymmetry, a theory that posits every known elementary particle has a heavier “superpartner” particle, has been the superstar of theoretical physics for the past half century. Its proponents have seen it as the best hope for particle physics to solve long-standing mysteries such as dark matter. The skeptics have protested its privileged treatment in the absence of experimental validation. At CERN’s Large Hadron Collider (LHC), the world’s largest and most powerful particle accelerator, finding evidence for supersymmetry became the next great expectation after its ATLAS and CMS experiments discovered the Higgs boson. Βut despite more than a decade of searching, both experiments are still coming up empty.

Supersymmetry’s cultural grip on the field has been so strong that discerning the theory’s end—should it ever come—would be difficult. But now that moment might be here: the ATLAS and CMS teams no longer have working groups dedicated to supersymmetry.

Such working groups are the backbone of ATLAS and CMS research, organizing hundreds of analyses under thematic umbrellas. In the early 2010s, as the LHC’s proton collisions began, each experiment’s supersymmetry group was the favored avenue for “new physics” searches—and even enjoyed a protected status in terms of resources and attention. The idea that one day there would be no dedicated groups would have shocked many.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“Supersymmetry was a huge industry starting from the 1990s until around 2015. But the lack of a discovery of superpartners after the LHC upgrade to higher collision energy was a turning point for most of the community,” notes Adam Falkowski, a theoretical physicist at the Laboratory of the Physics of the Two Infinities Irène Joliot-Curie (IJCLab) in France.

An “Almost Biblical” Belief

To understand supersymmetry’s appeal, one must look back to the early 1970s. In an effort to reach beyond the Standard Model, the theory describing all known elementary particles and their relations, theorists in the Soviet Union and the U.S. pioneered supersymmetry as a possible way out, with its central feature being a proposed correspondence between the known particles and as-yet-undiscovered ones.

Theorists soon realized that the mathematical tools involved in “SUSY” (the theory’s commonly used nickname) could fix many vexing problems in physics. Posited superpartners were ready-made candidates for particles of dark matter, and SUSY offered possible routes for a theory of quantum gravity. Additionally, it served as crucial scaffold for string theory and was a key argument for building the LHC. As the number of peer-reviewed publications on SUSY soared, the theory became a cultural phenomenon, with savvy science communicators churning out books, articles and interviews touting its validation as an almost foregone conclusion.

“When I was a student,” Falkowski says, “the existence of SUSY was almost a fact for a bulk of researchers working on the topic. This certainly was reflected in hiring practices, and you had a large group of top researchers whose entire publication list was tied to supersymmetry.”

All the while, no experimental discoveries came along, and supersymmetric models grew notoriously unfalsifiable, mainly because of their arbitrary features. The models came with many variables with unknown values added by hand—and required fine-tuning to explain SUSY’s absence from the natural world. Calculations to predict the masses of superpartners were prone to upward revision after each null result across multiple generations of colliders.

“Physicists tend to be faddish, following trends,” says Nobel laureate Sheldon Glashow, a professor at Boston University and one of the architects of the Standard Model. “At times, belief in supersymmetry seemed almost biblical.”

Desperately Seeking SUSY

Nevertheless, the lightest superpartners in the simplest SUSY models should be within reach of the LHC’s collisions—otherwise they couldn’t address the problems they were invoked to solve.

In 2015 upgrades to the LHC nearly doubled the energy of its collisions to 13 tera electron volts, but the analyses kept coming up empty-handed—to the palpable consternation of proponents and opponents alike. Once-robust enthusiasm for SUSY began to wane.

Ripley Cleghorn; Source: INSPIRE (data)

Fast-forward one decade. Last year ATLAS restructured its research work, dividing the dwindling SUSY studies among three groups. This resulted in the group Higgs, Multi-Boson and SUSY searches (HMBS), created in October 2024. (Before that, the ATLAS team’s open call for naming this new group quickly devolved into scathing commentary, with an influx of suggestions such as “Novel Physics Explored,” or “NOPE,” and “Group of All Theories,” or “GOAT.”)

Similarly, at CMS two years ago, the SUSY group began taking on non-SUSY analyses (albeit ones looking at the same “signatures” that are typically associated with the hallowed theory—combinations of measurements that serve as the “fingerprints” of different physical processes in the collisions). Reflecting that shift, this January the group was rebranded as the more generic New Physics with Standard Objects (NPS).

“The group restructuring had two main reasons: make the search groups of the same size and have a signature-oriented mind [to] share ideas across analyses with similar methods,” says Cécile Caillol, a researcher at CERN and convener of CMS’s NPS group. About one third of the analyses in the new group are about SUSY, she adds. ATLAS’s HMBS convener Sara Alderweireldt, a researcher at the University of Edinburgh, offers similar motivations behind ATLAS’s reorganization and notes that HMBS’s work on SUSY is ongoing: “Our new group still very much includes a dedicated SUSY focus,” she says.

Falkowski, who is not involved with either group, offers his own translation: “There are simply not enough motivated people to keep the enterprise going,” he says. “Also, from the practical point of view, it makes little sense to keep supersymmetric searches in a separate box from other searches, as the techniques involved are often overlapping. All in all, it was the only sensible decision, given the evolution of the field.”

Big Bets

ATLAS and CMS alike have now looked at the signatures of the most straightforward models and seen nothing new, but there are always other possibilities. Howard Baer, a professor at the University of Oklahoma, explains that more sophisticated, highly plausible supersymmetric models exist, with subtle signatures that may yet be discerned in the additional LHC data in the coming years. “It is lamentable that the rise of simplified models in LHC analyses has led to diminished communication between theorists and experimentalists,” he remarks. The trouble, as he sees it, is that “novel but highly implausible theories are valued with equal weight alongside theories [such as SUSY] which solve fundamental problems in physics.”

Although many models are well motivated in theoretical terms, their almost limitless variety has long been a point of contention for SUSY skeptics. This vagueness is occasionally bypassed through bets: some prominent physicists have wagered on very specific supersymmetric discoveries at the LHC. Most have conceded, but some bets remain officially unresolved due to ongoing disagreements between the wagering parties about supersymmetry’s true status.

There is, however, a bigger wager at play that supersedes individual squabbles to encompass the entirety of particle physics: the bet that supersymmetry’s eventual success would ease the path to a new generation of even more powerful experiments. Instead, the non-discovery of SUSY, paired with the discovery of all predicted Standard Model particles, makes it harder to justify the major international investment required for any bigger, better accelerator. Glashow remarks, “The ground is well trodden, and nothing has shown up. Things will change if and when the next great collider is deployed…. We shall not see, but our children may.”

Even if a project materializes, another hard choice awaits: Should the collider focus on higher collision energies typically required to find new particles or on more precise measurements of known particles (such as the Higgs) to reveal new effects? A single machine can’t properly do both.

These thoughts are echoed in Falkowski’s stoic predictions: “For the entire physics beyond the Standard Model, there will be gradually less interest, less papers, less experimentalists involved, less searches for new particles,” he says. “The shift will be toward ‘precision’ physics, or away from ‘collider’ physics.”

And in the present, he adds, unlike in past decades, a researcher working entirely on SUSY will no longer be popular in the job market. Baer similarly notes that few young physicists make funding proposals for SUSY searches.

The extensive length of a fruitless collective pursuit might be casting its shadow at this point. But it might also prove to be SUSY’s greatest legacy by informing a change in the way things are done. Borrowing from a different field, in the words of home-tidying expert Marie Kondo, “When you come across something that’s hard to discard, consider carefully why you have that specific item in the first place…. If you bought it because you thought it looked cool in the shop, it has fulfilled the function of giving you a thrill when you bought it…. it has [also] fulfilled another important function— it has taught you what doesn’t suit you.”

Regarding ongoing LHC searches, one thing is certain, as an ATLAS physicist commented online last September, “SUSY is still a nice theory, [but] it no longer makes sense to consider it a privileged theory compared to others.”