Among the slew of actions that President Donald Trump has taken during his first weeks back in office has been a barrage of attacks on federal scientists and scientific funding. The administration’s science agencies have fired thousands of employees, attempted to freeze research disbursements and proposed new policies that would reduce funding into the future.

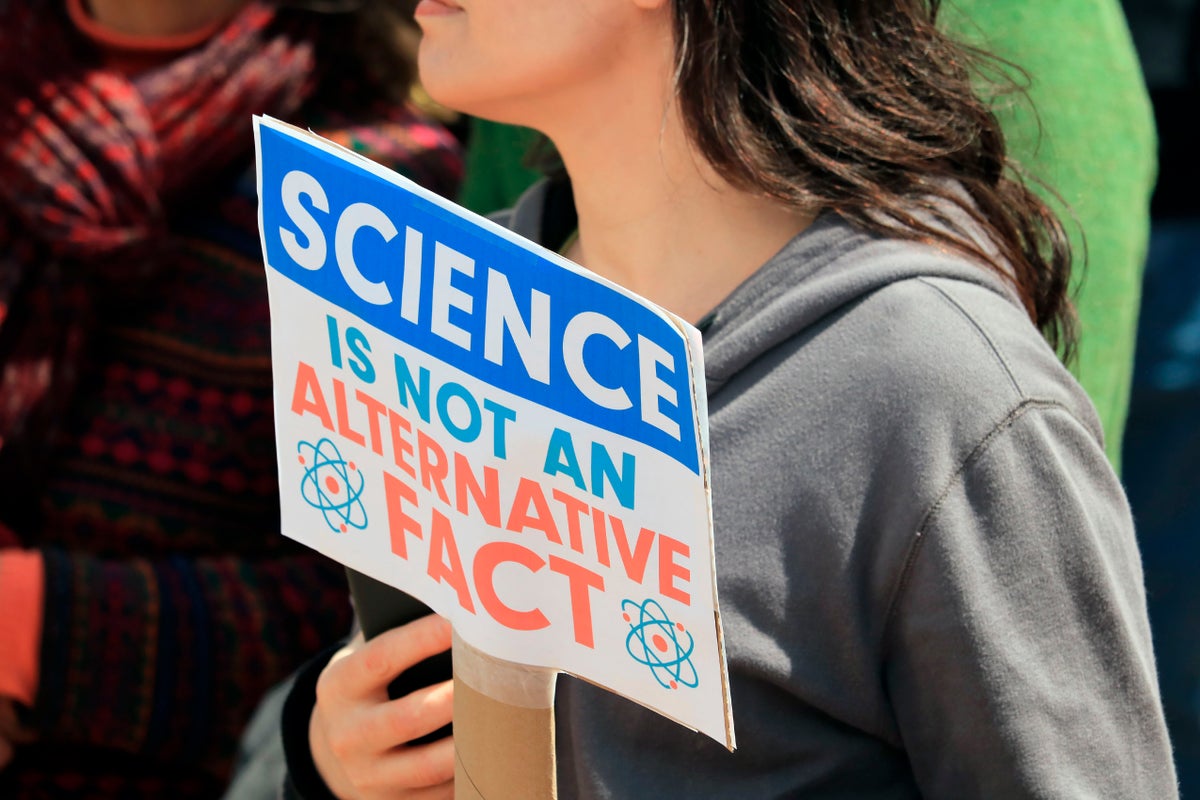

Against this backdrop, a team of early-career researchers is organizing nationwide rallies on March 7 to “Stand Up for Science”—a call for people across the U.S. to demonstrate to show their appreciation of science and its benefits to society. Rallies will take place in Washington, D.C., Chicago, Boston, Philadelphia, Seattle, Nashville, Tenn., Austin, Tex., and many other places across the country. The network of stationary rallies is set to take place eight years after the March for Science protests that met Trump’s first administration—which Stand Up for Science’s organizers hope helped prepare scientists to wade into politics.

To learn about Stand Up for Science’s plans and goals, Scientific American talked with three of its lead organizers: Colette Delawalla, a Ph.D. candidate in clinical psychology at Emory University, Emma Courtney, a Ph.D. candidate in biology at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, and Sam Goldstein, a Ph.D. candidate in health behavior at the University of Florida.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

[An edited transcript of the interview follows.]

How did each of you come to this place of wanting to step into activism?

DELAWALLA: I was just really mad. At the end of the day, I just want to do my research. I really think that studying addiction is important, and all science is important. But it really hit home for me, personally. I was angry, and it just seemed like everybody else was angry, too, and nobody else was doing anything about it. And, you know, “be the change you want to see in the world,” as cheesy as that is.

Are you connected at all to the 2017 March for Science?

DELAWALLA: Nobody in our core leadership team overlaps with people who were in the March for Science core leadership team. But we have been in contact with a number of the organizers from that group, and they seem to be really supportive and kind and generous with their advice and time and connections. And we’re so grateful.

We really appreciate that they were so ahead of their time in understanding that what was coming down the pipe in 2017 was really serious. They laid the groundwork for people to have a working conception of what it means for scientists and people who believe in science to come together. Without that foundation, I don’t know that we would have had as much success.

GOLDSTEIN: It feels sort of like a passing of the baton—we probably wouldn’t have known where to really start.

COURTNEY: What I have found really impactful in talking with the March for Science organizers is the event, day of, is really important. But it’s also about building a sustained movement that actually drives policy change.

“We’re trying to give folks somewhere they can feel powerful and have their voices heard.”

What does a successful day on March 7 look like for you?

DELAWALLA: We want thousands and thousands of people to come. All over the U.S., we want people to put down their science, put down the pipette, close their R script, cancel their run-throughs of their experiments that day and come out. That is our number one goal for March 7.

Additionally, we want this to come up on the public’s and our government representatives’ radar. We do have plans to be meeting elected officials in Washington, D.C., in the week leading up to the rally. The goal is that we start off with a bang. This is sort of the science block party to really launch the demands into public view and to start the work on seeing them met.

GOLDSTEIN: It feels like this is only the beginning of the conversation. This is really just, across America, giving folks that maybe feel a lot of despair across this first month an outlet to feel heard and understood and comforted by like-minded individuals. Despair can sometimes breed apathy. The more it hits you, the more you doomscroll, the more you just feel powerless. We’re trying to give folks somewhere they can feel powerful and have their voices heard.

DELAWALLA: The other thing is that we are trying to get a good plan for what happens on March 8. What are the actions that we’re going to take? What are actionable steps we’re going to present to scientists and the lay public in America to help us get closer to meeting our demands?

There are people who believe that science is supposed to be apolitical. How do you respond to that? Did you ever have that mindset?

DELAWALLA: I study addiction, so I’ve never experienced science in a nonpolitical way. That said, I believe that science is political but not partisan. We are not drawing partisan lines here. We’re happy to explicitly say that the executive orders that have been signed into action are negatively affecting science very, very broadly. Historically speaking, science has had support from both sides of the aisle. People in all areas understand that scientific progress in America is a crown jewel of our progress as a country. And so, for me, it is inherently political. It is not partisan, though, and I think that that’s a key nuance.

COURTNEY: The way that we’re taught science is really meant to minimize the role of opinion and bias in data collection. But I think that is kind of the limit to which science is not political.

Politics defines who can be a scientist. Politics defines which grants get funded and what gets attention. Science and politics are really incredibly intertwined. The modern science enterprise was born after World War II because it kind of created an American edge on the global order. And I think that’s something that scientists have removed themselves from in some ways.

More than 500 people picketed in Seattle during the Hands Off Our Healthcare, Research and Jobs rally on February 19, 2025.

James Anderson/Alamy Live News

As earlier-career researchers, do you have concerns about how people in the field might respond to you now that you’re taking a step that some of them wouldn’t take or wouldn’t believe was appropriate?

DELAWALLA: We’ve been fortunate in just the sheer amount of support that we’ve received publicly and also behind the scenes. At the same time, of course, this is a career risk: we’re early career scientists, and we’re attaching our names and faces to this movement, and that is inherently risky. We waited for somebody to stand up. We waited for people to employ their tenure, to employ their safety, to lead this movement.

Frankly, I don’t know that there’s going to be a job market if we don’t take some pretty extreme action. This is a five-alarm fire. I want to have a job as a career scientist—research is my passion, and I want to do it as a career. If we don’t take a minute to pause our science and to stand up for what we believe in and try to push for policy change, that’s not going to be there. It feels really important at our stage to make sure that we’re doing what we can to make sure that we can be scientists.

GOLDSTEIN: We just so happen to have enough passion, rage and commitment to do it. If this is a career risk, ultimately—and maybe this is a privileged position—but if this somehow derails my career, then maybe this isn’t where I was meant to be. I’d rather have it derail my career and let it open the doors for others to have the career they want than not do anything.

“I think there’s too much to lose if you don’t do anything right now.”

COURTNEY: Early-career scientists are in a really unique position at the moment because we’re facing almost the biggest threat to our future careers. And we’re not tied to a leadership position, an institution or federal grants that are at risk of, like, being pulled.

I think there’s too much to lose if you don’t do anything right now.

What sort of response are you getting, both from other scientists and from nonscientists?

DELAWALLA: Within science, a very, very, very strong positive response. We have been so pleasantly surprised with how far and wide this information has spread. I think we still have a lot of ground to make in terms of getting support from nonscientists and the lay public. We’re really working on that as our focus over the next two weeks.

GOLDSTEIN: I would say science is the common thread that links all of these various issues that seem like attacks against democracy. Even though we have a pretty specific platform, it still speaks to a lot of people that maybe have seen innovation and ideas and freedom seeming to be attacked under this. It’s broader than just science, but science is the common thread through a lot of these things.

On your website, you lay out ambitious policy goals: secure and expand scientific funding, end censorship and political interference in science and defend diversity, equity, inclusion and accessibility in science.

DELAWALLA: We would just like to acknowledge that these may feel like really big asks, given the current climate, and at the same time, no, they’re not. They’re not. We firmly believe that scientific funding is critical to American advancement. So we’re not coming to the bargaining table asking for just what we had before because we actually needed more funding before all this started in the first place. Our intention is to be bold.

COURTNEY: There’s a lot of rhetoric around inefficiencies within the American science enterprise right now. And I don’t really want to give those any weight. Investing in science has a very high return to the American economy. We advocate for science because it’s a personal thing that we believe is good. But it’s also a really good economic investment.

How can people get involved?

DELAWALLA: The best way you can get involved is to spread the word. We have the press release and printable flyers available. Tell all of your LISTSERVs, tell all of your friends and family, post it on your social media, send the press release to your department. That is the easiest and most effective way that you can help.

Make a plan to come out; plan your signs; make it a fun lab event. And if you want to get more involved, go check out our website.

COURTNEY: We also really want to put out options for people who can’t make an event on March 7 to also engage in advocacy, so we’ll be posting resources online for that.

Any final thoughts?

GOLDSTEIN: We’re excited to see folks come out, and we hope people show up for Stand Up for Science.

COURTNEY: I think, a lot of times, people who don’t know a scientist kind of think it’s secretive work that goes on far away that they can’t really relate to. But science is here for you and to serve you and to benefit your community. And scientists are just people that are your neighbors and friends and coworkers.