[ad_1]

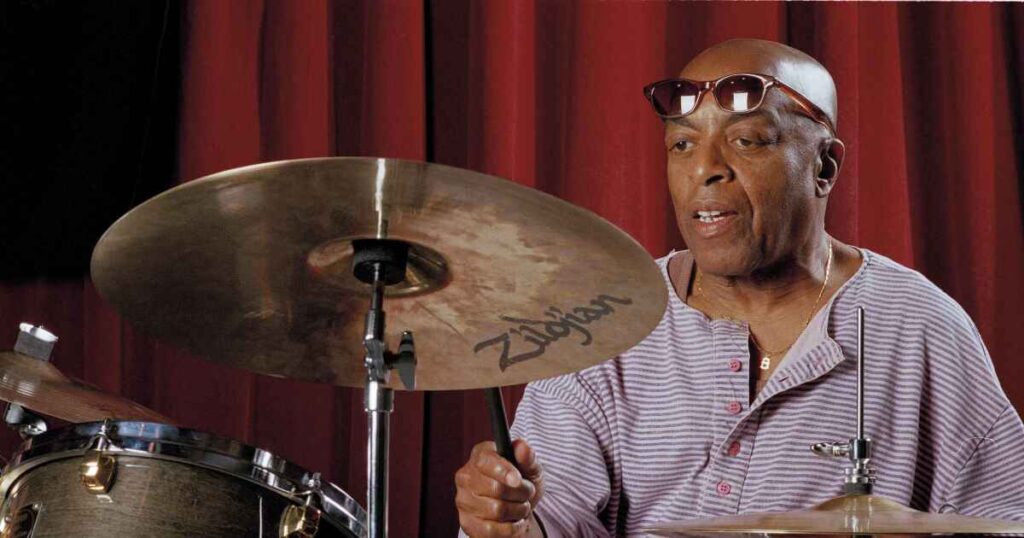

Roy Haynes, a jazz drummer and band leader whose skill and versatility led to performances with such diverse artists as Louis Armstrong, Charlie Parker, Chick Corea and Pat Metheny over the course of his seven-decade career, has died.

A representative for Haynes confirmed to The Times that the prolific percussionist died Tuesday. His daughter, Leslie Haynes-Gilmore, told the New York Times her father died after a brief illness. He was 99.

Haynes’ far-reaching résumé boasted expertise in most of the stylistic areas of jazz history. Called upon to play New Orleans music, swing, bebop, avant-garde, fusion, modal jazz, jazz rock, acid-jazz and more, he responded with extraordinary skill and imagination.

“One can hear the essences of all of those bandstands, concert jobs, dances, parties and jam sessions in the freedom of his beat and command of tempo,” critic Stanley Crouch, a drummer himself, wrote for the online magazine Slate. “Haynes,” he added, “has no date on the way he plays. It is and always was contemporary.”

Haynes’ remarkable longevity as a performer was underscored over the decades whenever he played at New York City’s venerable jazz club Birdland. In December 1949, he was the drummer with the group that opened the room — the Charlie Parker Quintet, with guest vocalist Harry Belafonte.

His playing from the ’40s, when bebop was becoming the principal jazz dialect, still sounds remarkable. Along with such contemporaries as Kenny Clarke, Max Roach and Sid Catlett, Haynes helped transform the drums from their traditional time-keeping role into a crisp assemblage of percussion and cymbal sounds designed to keep the music alive and thriving.

The high quality of his work from that period is apparent on such classic recordings as Parker’s “Anthropology,” Miles Davis’ “Morpheus” and Bud Powell’s “Bouncing With Bud.” Often called “Mr. Snap, Crackle” in tribute to his brisk, articulate drumming style, he wrote a signature tune with the same name for his own 1962 album, “Out of the Afternoon.”

What made Haynes different from many of his contemporaries, however, was his constant musical receptivity and adaptability. As new attitudes and styles arrived — the avant-garde of the 1960s, the fusion of the ’70s and ’80s — he quickly grasped their techniques and incorporated them into his own persistent musical vision.

Haynes “has a way of being inside the musical moment with a depth that is truly rare,” Metheny told the Philadelphia Inquirer in 2003. “He has a listening sensitivity that allows him to not only play beautifully every time out, but to make the musicians around him become the beneficiaries of his musical wisdom.”

Roy Owen Haynes was born March 13, 1925 in Roxbury, Mass. His parents, Gustavus and Edna Haynes, had moved to the area from Barbados. Roy was the third of four children, all boys. His older brother Douglas was a trumpet player who introduced him to jazz. Another older brother, Vincent, was a photographer and football coach, and younger brother Michael served several terms in the Massachusetts Legislature.

Haynes was still in his teens when he made his professional debut in the early 1940s. By mid-decade, he was playing with a variety of swing bands, as well as the Luis Russell big band — one of his rare extended associations with a large ensemble.

By the late ’40s, he had become a member of the group of arriving new young players associated with bebop. In a remarkable string of gigs, he successively played with Lester Young, Bud Powell, Miles Davis, Charlie Parker, Sarah Vaughan and Thelonious Monk. In the ’50s, he was with George Shearing, Stan Getz, Kenny Burrell and Lambert, Hendricks & Ross. From 1961 to 1965, he filled in as Elvin Jones’ substitute in the John Coltrane Quartet.

In his early career, Haynes was not as highly visible to the broader jazz audience as Max Roach, his senior by a little more than a year. In part, that can be attributed to the fact that Haynes rarely led his own groups, spending most of his time as a first-call sideman. He once jokingly pointed out that he was far more concerned with making sure his mortgage payments were made than he was with establishing himself as a leader.

But Haynes was always universally admired by other drummers.

“What Roy has as a musician is a very, very special thing,” drummer Jack DeJohnette told Smithsonian magazine in 2003. “The way he tunes his drums, the projection he gets out of his drums, the way he interacts with musicians onstage: it’s a rare combination of street education, high sophistication and soul.”

Despite his relatively low visibility, Haynes’ complex but always swinging style has had a significant impact — first upon the playing of such otherwise highly original drummers as Jones, DeJohnette and Tony Williams and in more recent years on Jeff “Tain” Watts, Eric Harland, Matt Wilson and others.

Small and compact, always fit, Haynes balanced his sophisticated drumming with an equally stylish wardrobe. Esquire magazine, in 1960, listed him as one of the best-dressed men in America, along with Clark Gable, Fred Astaire and Cary Grant.

In the last of his playing years, Haynes frequently led a changing group of musicians in a band known as the Fountain of Youth. It was an appropriate title, given the fact that the musicians he chose to work with were often three and four decades younger. But from his seemingly ageless perspective, when it came to making music, there were no differences.

“When we get on the bandstand,” he told the Albany, N.Y., Times Union in 2007, “we all become one age — the same age. It has nothing to do with how old you are or where you’re from, it’s what you can do musically.”

Haynes, who was named a National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Master in 1995, is survived by his daughter and two sons: Graham, a jazz cornetist, and Craig, a drummer. His grandson Marcus Gilmore is also a drummer. Haynes’ wife, Jesse Lee Nevels Haynes, died in 1979.

Heckman, a longtime jazz critic for The Times, died in 2020. Staff writer Alexandra Del Rosario contributed to this report.

[ad_2]

Source link