[ad_1]

Wild guess: You’ve probably heard of Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519).

The Florentine Renaissance artist, engineer and polymath made the most famous picture of all time, a painted poplar panel that hangs in virtual isolation in the Salle des États at Paris’ Louvre Museum. Now he’s the subject of documentarian Ken Burns’ new two-part film, made with daughter Sarah Burns and her husband, David McMahon, which has its debut Monday and Tuesday on PBS. Leonardo is Burns’ first non-American subject.

At the Louvre, the world’s most visited art museum, it is no longer possible to see “La Gioconda,” that famous picture better known as “Mona Lisa.” The museum’s chief curator has lamented that “it looks like a postage stamp.” The painting is barricaded behind thick bullet-proof glass. A wide wooden railing keeps probing eyes several feet away, and a deep buffer of camera-wielding tourists jostles for a snap to prove that they’d been in the presence of — well, not divinity, exactly, but close enough. The painting, begun in 1503, is everything it’s cracked up to be.

And cracked it is, a fine web of fractures disrupting the once soft and seamless surface — inevitable in an oil painting on wooden panel of its ancient age. The composition is constructed of materials that expand, contract and shift in response to the same weather that would have affected the craggy mountain landscape unfurling in the atmospheric background behind the seated subject: Lisa Gherardini, wife of local silk merchant Francesco del Giocondo, who probably commissioned it. Leonardo had considerable practice rendering nature, having made what is arguably the first pure landscape drawing in Western art — a pen-and-ink view down the Arno River valley, seen from a high vantage point — exactly 30 years before.

A favorite detail in the painting is Lisa’s twisted shawl, slung over her left shoulder so that the soft fabric’s curving shape flows directly into a hard stone cliff jutting out far beyond the equally hard stone window ledge immediately behind her. It’s a subtle visual leap across vast space. Leonardo moves indoors outdoors, as tactility and material substance magically rhyme and transform.

He even tells us what he’s doing. Along the silky shawl’s upper edge, Leonardo traced a razor-thin arc of reflected light that leads directly into a graceful background bridge across a river, linking near and far.

Leonardo had done such sorts of composition before, most notably in the exquisite “Lady With an Ermine,” a portrait of the Duke of Milan’s beautiful 16-year-old mistress. Her head and body aim in opposite directions, as if she’s just heard her name beckoned from behind as she was passing by and is turning to look. By contrast, the textile trader’s seated wife, neither a religious leader nor an aristocrat but a prosperous secular citizen of Florence, seems to have been posed precisely so the artist could connect her experience to the wider world out the window, gliding on a ribbon of light. Presumably Lisa’s husband, Francesco, a ruthless businessman with powerful roles in civic government amid the local oligarchy, was pleased.

No wonder the figure’s three-quarter view cemented the standard for European portraiture for centuries, replacing frontal or, more often, profile poses that harkened back to classical Greece and Rome. (Remember all those ancient coins with ruler portraits in profile?) The painter was well-versed in ancient literature and philosophy, and he was instrumental in establishing a new European idea of art as a living, evolving, intellectual activity, following centuries of craft-based medieval practice. His Lisa lives now.

Burns’ documentary doesn’t examine this particular shawl detail, although many other bits in different pictures are scrutinized. In fact, those are among the program’s most absorbing moments.

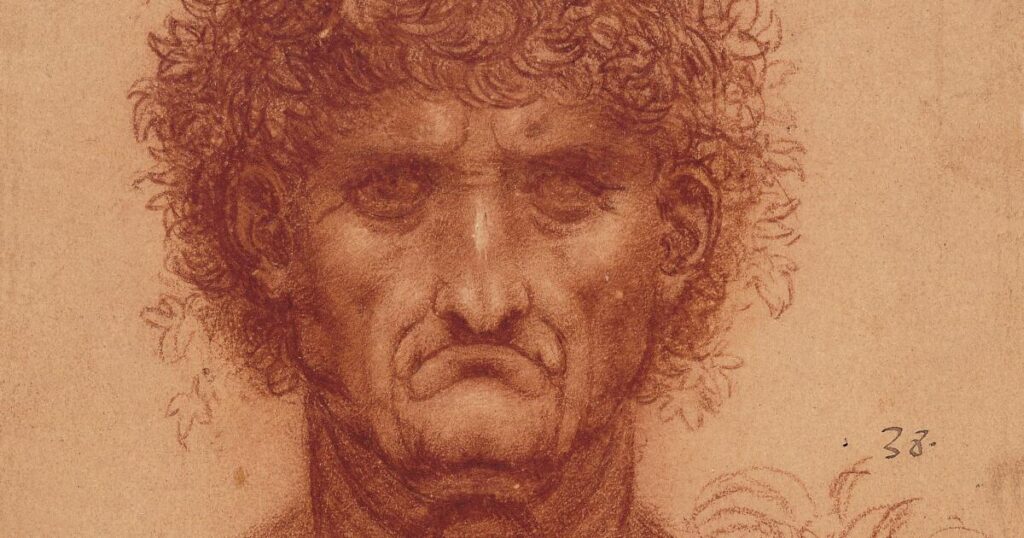

One dives deep into the strained but anatomically accurate neck muscles and sharply delineated collar bones of St. Jerome, shown praying in the bleak wilderness. In the unfinished painting, the tormented saint tilts his head far to one side, capping a long diagonal line made from an outstretched arm that cuts across the picture. A wholly unexpected focus on those modest and hidden internal body parts in his neck insinuates Jerome’s interior anguish, an emotional experience that cannot be seen inside his head.

The most fascinating is the complex compositional analysis of the figures in Leonardo’s second most famous painting, “The Last Supper,” that vast fresco in a communal dining room of a Dominican convent in Milan. Multiply and expand Jerome’s neck detail times 13. What the documentary describes as the “shock wave” from Jesus’ doleful announcement of profound betrayal within his cohort is seen rippling through the facial features and bodily gestures of the gathered apostles. The usual sober pageantry with which prior artists told the grim story is replaced by a brilliant choreography of chaotic harmonies. Tumultuous feeling fuses with formal gravity.

Fewer than two dozen autograph paintings by Leonardo are known. (He was notorious for procrastination, preferring to follow his own wide-ranging interests in science, machinery and the natural world over the desires of patrons.) Several more are referred to in historical texts or preparatory drawings but are now lost, while a few paintings are the subject of ongoing arguments as to their authenticity. The most widely known of the latter is “Salvator Mundi,” a seriously damaged and repainted image of Christ raising a hand in blessing that was captured for $450 million at a 2017 auction by Saudi despot Mohammed bin Salman. This and other disputed works are reasonably ignored in the documentary, which already has a lot of ground to cover.

Indeed, the first two of the program’s four hours can get a bit wearying, since it’s necessary to set up a complex mix of biography and history as background during a period of profound social and cultural transformation in northern Italy. “The Disciple of Experience,” as Part 1 is titled, chronicles the artist’s formative years and development of working methods.

Rather too much time is spent repeating staged close-ups of a left hand sketching in ink or applying paint, or else executing inscrutable mirror-writing on parchment — Leonardo’s secretive signature method — coupled with explanatory voice-over. (Keith David, triple Emmy winner for Burns’ documentaries on World War II, Jackie Robinson and Jack Johnson, is the able narrator.) Geometric order and water’s fluid movement were special fascinations. The worthy effort to emphasize that much of the artist’s inventive genius — unfurling in thousands of manuscript pages, rather than oil paint and tempera — makes the dull staging a perhaps unavoidable conceit.

The cast of Renaissance characters is also large and somewhat ungainly, populated with outsize historical players that include Michelangelo, Savonarola, Raphael, Niccolò Machiavelli, Cesare Borgia, various popes, assorted Medicis and many more. Excellent art historians, museum curators and writers — Martin Kemp, Carmen Bambach, Serge Bramly and others — are tapped for effective interviews, along with knowledgeable practicing artists such as painter Kerry James Marshall and theater director Mary Zimmerman. Part 2, “Painter-God,” is the more satisfying, zeroing in on the experimentation that drove his unique art and engineering, which fantasized flying machines, weapons of war and designs for urban infrastructure.

What gets short shrift, however, is Leonardo’s homosexuality. That essential element of his identity is presented as merely neutral fact, rather than the alienating circumstance it no doubt was. (A recent CBS “Sunday Morning” preview story ignored the subject altogether.) A small-town kid born out of wedlock, he moved from the rustic countryside of Vinci, 30 miles west of Florence, to the sophisticated city to make his way. There he acted on his same-sex attraction. Illegitimate and homosexual, he was doubly outside the era’s accepted social norms.

Leonardo, reportedly something of a looker, was arrested at 24 for sodomy with 17-year-old Jacopo Saltarelli, a male prostitute. (Charges were later dropped.) At 38 he took in as a studio assistant Gian Giacomo Caprotti, the impoverished 10-year-old child of a tenant farmer, who later became his lover and managed his business affairs for the rest of Leonardo’s life. (The pretty but unruly boy was soon nicknamed Salaì, a slang contraction of Saladin, the Kurdish Muslim sultan who famously quashed Europe’s 12th century Crusaders in Jerusalem.) And Francesco Melzi, the handsome and erudite 14-year-old son of a Milanese nobleman, became his painting apprentice and intellectual confidant when Leonardo was 53, remaining with him and compiling his voluminous papers until the artist’s death at 67.

All this is duly noted in the documentary, yet the implications for his creativity are not examined. Surely Leonardo’s erotic and emotional subjectivity within a repressive milieu was not nothing in shaping his worldly explorations — especially as a “disciple of experience” — but Burns doesn’t go there.

Penn State scholar Christopher Reed once pointed out that Dante dubbed sodomy “the vice of Florence.” Two hundred years later, around the time of Leonardo’s late-15th century arrest, fully one-quarter of the city’s male population — hundreds of men every year — had run afoul of the antisodomy laws. A stark, yawning gap separated private behavior and deep-rooted public morality.

It would be a mistake to assert that Leonardo made art as an expression of his identity, sexual or otherwise — a cultural concept that wouldn’t fully emerge until the modern era. (Even the codified term, homosexual, didn’t exist until 1892, although same-sex behaviors have always been with us.) The stage for his artistic blossoming was set in 1482, when he left the rich mercantile city of Florence for the cruder, more bumptious northern city of Milan. The great 2011 exhibition “Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan” at London’s National Gallery argued persuasively that, as court painter gainfully employed by the city’s ruler, he found the security and freedom, previously unavailable, that allowed his talents to blossom.

The question is worth asking: Could Leonardo, a brilliant, innately gifted homosexual denied full urban citizenship given his illegitimate birth status, have had a more powerful — and unprecedented — frame of reference for considering both art and the natural world as something radically different from what had been assigned in European culture? Given the artist’s transformative impact, I wish this otherwise engaging documentary asked it.

[ad_2]

Source link