David Medalla, a Filipino artist who died in Manila in 2020 at age 82, is not well known in the United States. “A Stitch in Time,” perhaps his most widely admired work, was an interactive, multiyear piece that he began in London in 1968 by inviting the audience to sew small objects, images or texts of personal significance onto a large cloth suspended in a public space. Its 1998 inclusion in “Out of Actions: Between Performance and the Object, 1949-1979” at the Museum of Contemporary Art is one of the few times Medalla’s art has been shown in Los Angeles.

Now, the UCLA Hammer Museum is presenting “David Medalla: In Conversation With the Cosmos,” organized by interim chief curator Aram Moshayedi, the first American retrospective of the artist’s work and a curiously absorbing affair. “A Stitch in Time” is not included (some documentary material related to it is, including a drawing and a tin box stuffed with bits of cloth and spools of thread). With just a few sculptures and paintings, the show is largely composed of works on paper — scores of drawings, watercolors, notations, sketchbooks, posters, notepads, photographs, scrapbooks and other assorted ephemera — plus documentary photographs by colleagues. The most frequent material Medalla employed over the course of half a century seems to have been ballpoint pen.

Did I mention that his drawings tend to be pretty terrible? They are — at least in the traditional sense of skillfully developed and captivating rendering, or what has been called “artisanal competence” (sometimes derisively). Looking at them is sort of like rifling through the diary of someone with really poor penmanship.

His drawings are rarely where he worked out the look of a painting or sculpture, and none seems to have been intended as a standalone art object. The data can be interesting, even if the look is unripe and sometimes crabbed. The show’s primary exceptions are three vivid, colorfully explosive 1962-63 studies for an impossible sculpture-machine that would ooze molten lava into random patterns — Earth’s primal forces simultaneously destroying and creating.

Perhaps the studies were inspired by contemporaneous, widely reported activity of Hawaii’s dramatic Kilauea volcano and the epic, year-long eruption of Gunung Agung volcano in Indonesia. Volcanic action is hardly uncommon in the Philippines. Whatever the case, with magma running at 1,300 to 2,200 degrees, production of an actual lava sculpture-machine was unlikely. The imaginative drawings entice.

In a notebook entry, Medalla explains that he began to draw in 1943 at age 5, during the brutal Japanese occupation of Manila, when his four older siblings gave him a set of watercolors, colored pencils and pads of paper to play with. He kept at it until he was felled by a stroke in 2016. There’s no indication that he ever developed facility with it.

Nor is there any indication that he wanted to. What begins as rudimentary contour drawings of figures in flat black ink, including male nudes and the intertwined heads of kissing boys, is soon accompanied by scratchy ballpoint sketches, often on ruled paper, of things rumbling through the artist’s head. Images span performance ideas, political sloganeering, plans for kinetic art objects, fascinations with Rosa Luxemburg, the Polish German socialist thinker, Arthur Rimbaud, radical French poet, and more. That early childhood identification of the manual activity of drawing with feelings of social, homosexual and familial warmth repeatedly shines through the exhibition.

It also lurks within the absent “A Stitch in Time.” That participatory project was birthed by serendipity. Medalla had given embroidered handkerchiefs, needles and thread to two ex-lovers, urging them to add embroidery to the cloth at their leisure, in any way they liked. Years later, in a random encounter in Amsterdam with a backpacker from Bali, Medalla discovered one of those handkerchiefs in his possession.

Maybe by chance, the original launch of “A Stitch in Time” also coincided with a landmark labor-relations dispute in the United Kingdom, in which sewing collided with tangled questions of gender and skill. (The peripatetic Medalla lived and worked primarily in London, where he co-founded Signals Gallery, with stints in Paris, New York and Berlin, and he traveled widely, returning periodically to Manila.) London’s 1968 sewing machinists’ strike at a Ford factory, led by six women, caused a huge public uproar when the auto company sought to cut wages for the women’s “less skilled production job” of sewing seat covers rather than welding chassis. The women’s strike, ultimately successful, prompted passage of a national equal pay act.

Medalla’s performance actions sometimes employed fanciful homemade masks — amusing, although nothing special, based on the few displayed examples. Often, the actions took direct aim at social issues, including the shocking imposition of martial law in his previously democratic, post-colonial homeland. Tiered shelves in one Hammer gallery feature a few dozen collages on a rainbow of brightly colored poster boards — titled “Kumbum,” after the endless manifestations of Buddha’s bodies in Tibetan lore — each simply an informational newspaper story or full-page pasted down. Several include scrawled Medalla text that lambastes Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos, one for shutting down the resolutely liberal broadsheet, the Manila Chronicle, founded at the end of World War II.

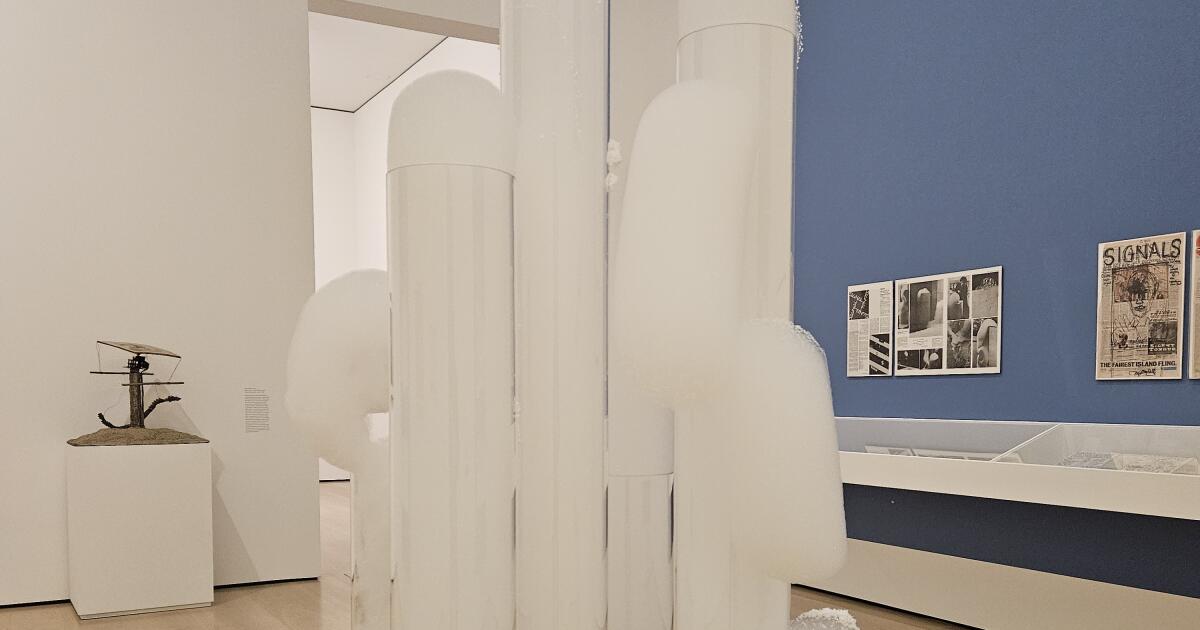

The show’s standout work, though, is “Cloud Canyons” (2017), one of a series of kinetic sculptures Medalla began exhibiting in 1964. Frothy clouds of soapy bubbles emerge from the tops of five clear plastic pillars, which rise from a circular platform that hides the bubble-compressors. Transitory columns of evanescent foam rise, droop and fall. The foamy shapes recall solid prewar sculptures by Naum Gabo, Constantin Brancusi and Jean Arp, while the kinetic machine creates ephemeral drawings in space, a motif of central importance in Western art after World War II.

Medalla said the work was inspired by personal experience, including an indelible memory of the scary frothing mouth of a wounded Japanese soldier he discovered in the family garden when he was a small child. Constructed right after his lovely but impossible drawings for an erupting lava-machine sculpture, the bubble sculpture is also inescapably erotic. The steadily oozing phallic cycle implies a sequence of erection, ejaculation and flaccid rest, only to endlessly repeat. That five climaxing columns cluster tightly together infers an abstract same-sex orgy — another primal force simultaneously destroying and creating.