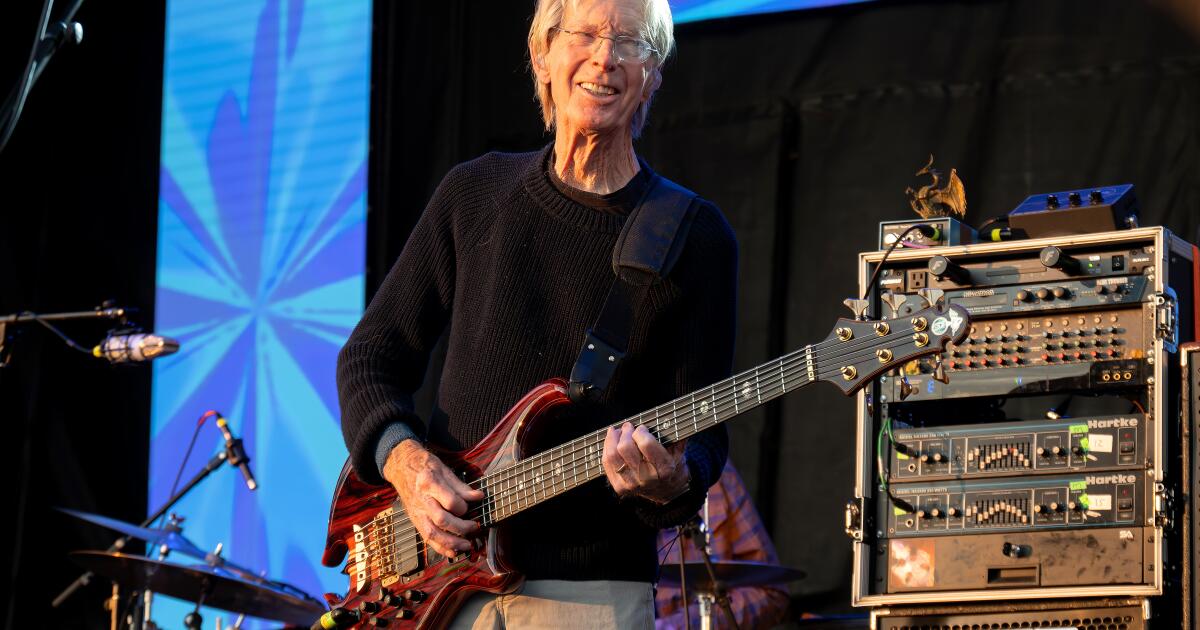

Phil Lesh, the bassist for the Grateful Dead who propelled many of its wildest musical explorations yet also composed and sang one of its loveliest songs, “Box of Rain,” has died. He was 84.

An announcement on Lesh’s instagram account went out on Friday: “Phil Lesh, bassist and founding member of The Grateful Dead, passed peacefully this morning. He was surrounded by his family and full of love. Phil brought immense joy to everyone around him and leaves behind a legacy of music and love. We request that you respect the Lesh family’s privacy at this time.” No cause of death has been reported at this time.

A classically trained musician who harbored an affection for jazz and the avant-garde, Lesh was something of an outlier within the Grateful Dead, a group whose two lead vocalists, Jerry Garcia and Bob Weir, were grounded in folk, bluegrass and blues. A rock ’n’ roll novice when he joined the nascent Dead in 1964, Lesh helped shape the band’s psychedelic aesthetic, especially during its early days when members devoted a portion of their time to exploring the possibilities of the recording studio. Although Lesh never lost his appetite for experimentation, he also honed his skills as a songwriter as the group re-embraced its folk roots on its pivotal early-1970s albums, “Workingman’s Dead” and “American Beauty.” “Box of Rain,” a tribute to Lesh’s late father that marked the bassist’s first lead vocal on a Grateful Dead record, was the pinnacle of this period, but he also had co-writing credits on “Truckin’,” “Cumberland Blues,” “St. Stephen” and “New Potato Caboose,” all crucial parts of the Dead’s songbook.

Grateful Dead biographer David Browne wrote of Lesh, “Beneath that affable exterior lay a taskmaster and perfectionist.” During the band’s first decade of fame, those tendencies manifested in the studio — he sculpted large segments of the aural collages on their second album, “Anthem of the Sun” — and on the stage, where he was one of the vocal advocates for their Wall of Sound, an innovative concert PA system that helped set the standard for arena rock, and also drove the band toward an extended hiatus from the road in 1975. Lesh later claimed that the Dead “was wildly successful for me until we took the break from touring [in 1975]. When we came back, it was never quite the same. Even though it was great and we played fantastic music, something was missing.”

Lesh remained with the Dead through their unexpected upswing in popularity in the late 1980s and early ’90s, a revival partially fueled by the band’s only Top 40 hit, “Touch of Grey.” He nevertheless was a bit of a diminished presence in the group’s later years, and neither wrote nor sang on the group’s final two studio albums. After the Dead disbanded following Garcia’s death in 1995 — a passing that came a year after their induction into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame — Lesh kept the group’s adventurous spirit alive through a series of musical offshoots, alternating between explicitly solo projects like Phil Lesh and Friends and teaming up with his former bandmates in the Other Ones, Furthur and the Dead. Throughout these excursions, he attempted to stay true to the band’s initial guiding spirit: “The major factor with the Grateful Dead doing what they did and what we’re trying to do still is the Group Mind. When nobody’s really there, there’s only the music. It’s not as if we’re playing the music … the music is playing us.”

Phillip Chapman Lesh was born on March 15, 1940, in Berkeley. Raised in the Bay Area by working parents, he spent many hours with his grandmother. Hearing broadcasts of the New York Philharmonic drift out of his grandmother’s room sparked a love for music. Lesh persuaded his parents to let him learn to play the violin, eventually abandoning the instrument in his early teens. He switched to trumpet, developing such an intense interest in playing that his parents moved the family back to Berkeley so he could take advantage of the city’s high school music program.

Growing up in Berkeley at the peak of the Beat era, Lesh spent time at bohemian hot spots such as the bookstore City Lights and the Co-Existence Bagel Shop. Initially, college was a bit of a struggle. He dropped out halfway through his first semester at San Francisco State, moving back home to attend the College of San Mateo, and soon transferred to the University of California, Berkeley. His interest in the Beats deepened, complemented by an interest in experimental music, a passion he shared with his friend, keyboardist Tom Constanten. Enamored by the works of Thomas Wolfe in college, Lesh briefly considered pursuing literature academically but he was drawn back to music. Stravinsky’s “Rite of Spring” opened a door, as did the improvisational adventures of John Coltrane. He drew further inspiration from composer Charles Ives, claiming, “The music of Ives contains the world. … It sounds like the inside of your head when you’re day dreaming.”

Volunteering as a recording engineer at the noncommercial radio station KPFA, Lesh also spent time attending folk cafes, entering social circles that led him toward Garcia, a folk guitarist with a flair for bluegrass. After Lesh heard Garcia sing the ballad “Matty Groves” at a party in 1962, the pair became fast friends, leading Lesh to record a tape of Garcia that aired on KPFA. It would take a while before the pair chose to collaborate. Lesh dropped out of UC Berkeley and headed to Las Vegas in the summer of 1962, living with Constanten’s family until they’d had enough of the bohemian in their midst. Taking a Greyhound bus back to Palo Alto, Lesh whiled away a few years rooming with Constanten and working at the post office as he composed classical music. Early in 1965, he went to see the Warlocks — the folk-rock group Garcia formed with guitarist Bob Weir, drummer Bill Kreutzmann and keyboardist Ron “Pigpen” McKernan. Garcia wound up asking Lesh to join the Warlocks as bassist. The fact that Lesh didn’t know how to play bass and only recently had developed an interest in rock ’n’ roll, let alone shown an inclination to play it, caused no concern.

While learning to play bass in the Warlocks, Lesh developed an elastic, melodic style that became as much a Dead signature as Garcia’s winding guitar leads. Once Lesh discovered a single credited to another band called the Warlocks, he had the group and selected associates convene at his apartment to decide upon a new name — a process that came to a standstill until Garcia plucked “the Grateful Dead” from a dictionary.

The Grateful Dead made its debut at one of Ken Kesey’s Acid Tests in 1965. Over the next year, the band would be a fixture at these psychedelic events, cultivating relationships with such figures as their manager Rock Scully and Owsley Stanley, a manufacturer of LSD who helped keep the Dead afloat during their early years; under the moniker “Bear,” he’d become the band’s sound engineer, a passion he shared with Lesh.

By the fall of 1966, the Dead signed with Warner Bros. Records, the label giving the group artistic control as well as unlimited studio time. After quickly cutting the Dead’s eponymous debut album in 1967, Lesh and Garcia soon would take advantage of this clause, spending an inordinate amount of time experimenting in the studio for “Anthem of the Sun” — the first record to feature the Dead’s second drummer, Mickey Hart, as well as Lesh’s college friend Constanten, whose time with the band was brief — and “Aoxomoxoa,” an album they wound up recording twice as they adapted to a new 16-track recorder they acquired. Faced with mounting debt, the band took that 16-track recorder to capture live performances at the Fillmore West and the Avalon, making “Live/Dead,” the album that righted them financially with Warner while also capturing the open-ended improvisations the band played onstage.

Despite the promise of “Live/Dead,” the Grateful Dead remained on rocky ground in the early 1970s. Nineteen members of their entourage were arrested for drug possession in New Orleans in January 1970 — the event became part of Dead lore when lyricist Robert Hunter immortalized the bust on “Truckin’” — and they’d discover by the end of the year that Lenny Hart, father of Mickey, who was brought aboard in a management role, embezzled much of their money. During all this, the band was able to record two pivotal studio albums: “Workingman’s Dead” and “American Beauty,” lively, folk-inflected rock ’n’ roll records that contained many of the band’s enduring songs, including “Uncle John’s Band,” “Casey Jones,” “Friend of the Devil,” “Sugar Magnolia” and Lesh and Hunter’s “Box of Rain.”

The inner workings of the Grateful Dead remained fluid in the early 1970s, as the band sustained membership turnover — Mickey Hart returned to the group after an absence, Pigpen retired from the band a year before his 1973 death; his time overlapped with his replacement, Keith Godchaux, who brought along his wife, Donna, as a backing vocalist — and failed business ventures, such as running their own record label. Despite this turmoil, the Dead stabilized in some senses after the twin successes of “Workingman’s Dead” and “American Beauty” established the band’s parallel paths: Onstage they’d chart the outer limits of their sound while attempting to focus on songcraft in the studio.

During the first half of the 1970s, the two avenues proved equally fruitful, but after the triple-live album “Europe 72,” the scales started to tip toward the group’s stage work, at least for their legion of fans known as Deadheads. Deadheads traded amateur recordings of Dead concerts in a practice endorsed by the band. These recordings helped build their fan base throughout the 1970s and ’80s and sustained their popularity long after the band was an active concern. These live recordings had an appeal beyond Deadheads: The group’s May 8, 1977, concert at Cornell University was placed into the National Recording Registry of the Library of Congress in 2011.

The band’s success as a road act eventually caused strain on its members, especially after the cumbersome, expensive tour of 1974, where their music was piped through their custom-made “Wall of Sound,” consisting of more than 600 speakers standing 40 feet high and 70 feet wide. Lesh wrote in his memoir “Searching for the Sound” that “this period (about forty gigs) remains to this day the most generally satisfying performance experience of my life with the band,” but the costs of touring with the system were prohibitive. Once the tour wound down, the Grateful Dead decided to stop performing for the foreseeable future.

As Garcia busied himself with “The Grateful Dead Movie,” hoping a theatrical release of October 1974 shows at the Winterland would satisfy audiences wanting to see live Dead, Lesh entered an aimless period. After collaborating with electronic composer Ned Lagin on the 1975 album “Seastones,” he started to drift and consume too much alcohol. He later remembered, “I didn’t know whether (the band) was ever going to start up again. I’ll be honest with you — that drove me to drink. That fear. I didn’t have a future. I didn’t have any side bands. The Grateful Dead was my band. I helped create it.”

Although the hiatus didn’t last long, it was enough to shift the momentum for Lesh. No longer singing high harmonies — he’d damaged his vocal cords, a condition exacerbated by his alcoholism — Lesh also receded from songwriting, gradually feeling disconnected from the AOR-oriented albums the band made for Arista. He told Dead biographer Browne, “I wasn’t deeply involved in those records. I felt like a sideman.”

Lesh’s fog started to lift in 1982 when he met a waitress named Jill Johnson. Two years later, they married, eventually raising two sons. Family life suited Lesh: He stopped drinking and took his boys on the road. Lesh hadn’t been the only member of the Grateful Dead to battle substance abuse, but in the late 1980s, the entire group had a moment of collective clarity that coincided with the sunny, celebratory “Touch of Grey” becoming an unexpected hit in 1987.

“Touch of Grey” introduced a new generation of fans to the Grateful Dead, many much rowdier than the Deadheads who had followed the group through the years. “Its effects were dramatic,” recalled Lesh. “It brought in a number of young people who didn’t really have a feel for the scene and the ethos surrounding it, which was considerable after two decades. We were thrilled with the interest in the band, but it just stood everything on its head. More people wanted to see us, so we had to play larger venues. Playing in front of larger crowds resulted in a loss of intimacy, and for me the experience was all downhill from there.”

Garcia reacted to the increased attention on the Grateful Dead by retreating to the heroin addiction that led to his death from a heart attack on Aug. 9, 1995. The Dead disbanded in the wake of Garcia’s passing. Lesh quickly faced his own health problems: In 1998, he had a successful liver transplant after having a chronic hepatitis C infection. Lesh crept back into action with Phil Lesh and Friends, a collective built on Bay Area musicians that initially played benefit concerts. By 1999, he rejoined Bob Weir, Mickey Hart and latter-day Dead associate Bruce Hornsby in the Other Ones, but his tenure in the group was brief. He and drummer John Molo left in 2000 to concentrate on Phil Lesh and Friends. Warren Haynes, the Allman Brothers Band guitarist who played often with Friends around this time, said, “Phil faced down death and came out the other side and has basically decided to do exactly what he wants with no compromise. That means a band which maintains the Dead’s improvisational quality, while also being more structured.”

Phil Lesh and Friends proved to be successful, eventually outdrawing Weir’s band Ratdog early in the 2000s. Lesh led the band through one studio album — 2002’s “There and Back Again,” featuring songs co-written by Robert Hunter — but that wound up being his last collection of original songs. He returned to the Grateful Dead fold in 2003 as part of the Dead, a touring entity featuring all four surviving members of the original band. The Dead drifted apart after a 2004 tour, so Lesh turned his attention to “Searching for the Sound: My Life With the Grateful Dead,” an autobiography published in 2005. He spent 2006 successfully battling prostate cancer.

After receiving a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Grammys in 2007, the Dead reunited to play a pair of benefit shows for Barack Obama’s presidential campaign in 2008. Lesh and Weir continued with Furthur, which reconnected to the adventurous improvisations of the Grateful Dead’s spacier excursions. Furthur stayed together for five years, during which time Lesh and his family opened up a performing venue and restaurant called Terrapin Crossroads in San Rafael. Inspired by Levon Helm’s Midnight Ramble shows in Woodstock, Terrapin Crossroads featured many informal jam sessions headed by Lesh, who often played with his now grown sons as the Terrapin Family Band; he also brought incarnations of Phil Lesh and Friends to the venue.

Lesh decided to retire from touring after the disbandment of Furthur but he agreed to participate in “Fare Thee Well: Celebrating 50 Years of the Grateful Dead,” a collection of three concerts touted as the last time the four original surviving members of the Grateful Dead would perform together. Although Weir, Kreutzmann and Hart decided to soldier on as Dead & Company, Lesh opted out. He kept Terrapin Crossroads as his performing home base through its closure in 2021, stepping aside for various festival appearances with Phil Lesh and Friends, notably joining Wilco’s Jeff Tweedy and Nels Cline to play a set as Philco at the Sacred Rose Festival in 2022.

Lesh is survived by his wife, Jill, sons Grahame and Brian and grandson Levon.