[ad_1]

The season finale of “American Sports Story” laid bare the tragic end for Aaron Hernandez, that once promising NFL player. Closing out the 10-episode season, the FX limited series dramatized the final days in prison of a young man haunted by ghosts and riddled with guilt, who saw death as the only possible release from his inner demons (and his pending legal woes regarding various murder indictments).

The episode, titled “Who Killed Aaron Hernandez?,” shies away from simple answers to that question. Instead, it stresses how internalized homophobia, toxic masculinity, an emotionally stunted father figure, an NFL team eager to coddle its players — not to mention the effects of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), courtesy of a lifetime on the field — all played key roles in the violence that doomed Hernandez’s life and career.

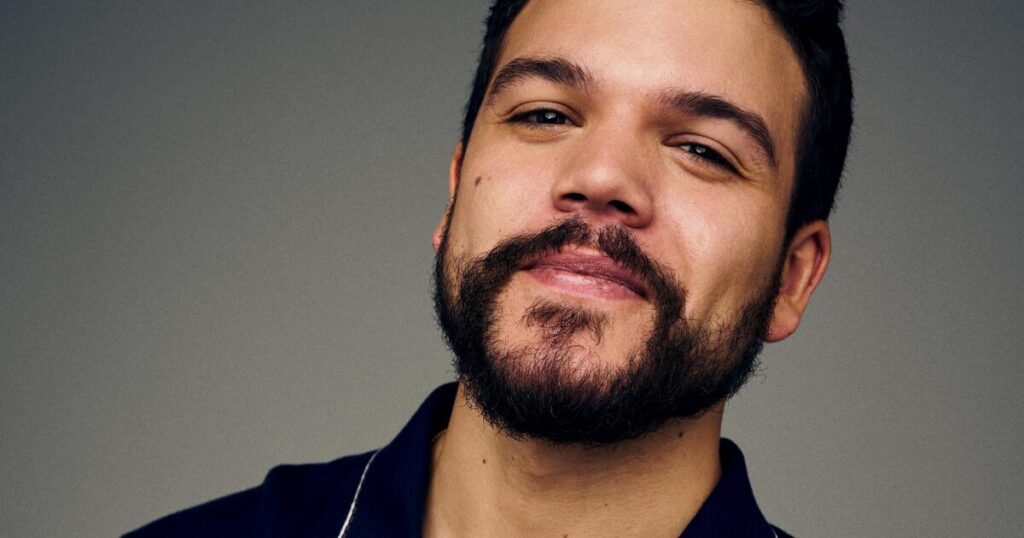

And front and center, in the show, was Josh Rivera. The actor, who previously starred in “West Side Story” and “The Hunger Games: The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes,” skillfully anchored his portrayal of Hernandez in the many contradictions that afflicted the Connecticut-born player through his brief life (he died at just 27 years old). In his hands, Hernandez could be both the irascible macho guy who fired shots in cold blood at strangers and friends alike, as well as the doe-eyed, wounded boy who just wanted to be loved by his dad and found comfort in the arms of other men (away from the eyes of his fiancee).

Rivera talked to The Times about the finale, the work that went into creating a complicated portrait of a figure many have judged based on the headlines that followed his imprisonment and death, and why he’s slowly learning to bask in the praise that’s been heaped on him for this breakout performance. This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

How has it felt seeing the show now come to an end?

It’s just been a really interesting experience. There’s just a lot of first times that are happening for me right now. Because I’ve also never done an entire series, which is a whole different muscle in itself. It’s been really relieving for it to just be out. I mean, it’s out of my hands. There’s nothing I can do. And whatever people want to feel, they can feel.

And then, in general, career-wise, I have this thing that is probably not uncommon for actors to have, but every job that I do, I finish it and I’m like, “All right, it was nice while it lasted,” you know? “I guess that’s the end of the road.”

I have this unease perpetually about that. And now something I’m finding really exciting is the amount of conversations I’m having about developing stuff and being more involved in the creative aspects of things. This show was the first time I’ve ever felt like I got to take any sense of ownership over the overall product. I wasn’t a producer in it or anything, but I had an open line of communication with everybody who was creating it, which was the first time that’s ever happened for me.

This is quite an ambitious miniseries telling a rather complex story about a very public figure — all over the course of 10 episodes. As an actor, how did you approach knowing you’d be portraying Aaron from his high school years, then his football career and all the way through to his death?

I was nervous about that initially, but it ended up being monumentally helpful because you get to distinguish the factors that come together in the end a little bit more by depicting them chronologically. Because when you look at the end product, and when you look at all the press surrounding this figure, there’s just so many components that go into it.

You talk about sexuality. You talk about CTE. You talk about getting money really, really early. Getting fame, really, really early. You talk about the relationship with his dad. So when I was approaching the story, I was just like, I don’t know what to do. How do you make a characterization that’s at all specific when you have this many range of factors?

What was really nice about building this narrative was that we got to lay it brick by brick. Then over time, we get to the season finale, where all of these things are pulling at each other. It makes it a lot easier to trust the foundation that we’ve already built.

But I won’t lie, in the beginning, it was extremely intimidating. I didn’t really know how I was going to do it.

The one moment that most struck me, especially as a gay man watching, was the brief scene when he realizes one of his lawyers is gay and Aaron flat-out asks him who’d molested him as a child. It’s such a revealing moment for how Aaron understood his sexuality. How was it like teasing out that scene?

That scene makes me so sad. I don’t remember the context in which his lawyer told that story, but that’s a real story that his lawyer told and he expressed feeling a lot of sympathy in that moment toward Aaron. Because you don’t know the degree to which Aaron’s been keeping that to himself his entire life, and you don’t know how many things, how many assumptions, or how many choices have been built on that assumption to himself. I just thought it was really well written and it’s very important. But it’s rough.

Especially because I think one of the things the show stresses throughout is how loose and free Aaron could feel when he allowed himself to be open and tender with other men, like with Chris (Jake Cannavale). But he so rarely allows himself that.

And there is in a lot of different moments in the show, too, directly coming after those very real, tender moments, the feeling of failure. He feels like he has failed himself and others. To have that close, direct association — I mean, gosh, that can be really largely informative on the choices that you make. I’m glad that that read, because that was something that I know was very important to [writer and creator] Stu [Zicherman], to emphasize that authenticity in those moments, and feeling like there was a real part of himself that he could be in those moments. It’s very sad to see that associated with failure. I’m saying this, obviously, from the perspective of the narrative that we’re telling.

And a feeling of failure so tied to his father, who appears in this episode as a kind of hallucinatory vision in prison, which is also quite an affecting moment.

When I was reading the draft for the final episode, I got really excited when I saw that scene. Because I was like, “This is it. This is the big monologue.” Aaron is very short on words for basically the entire series, so it was exciting to be able to talk at length in a scene. I was like, what a beautiful moment to just lay everything out. I think it’s such a good bookend for his character because without it, the whole thing is just very, very dark. Narratively, I think, just as a consumer, you want something that’s just even a little bit like a period. There’s some acknowledgment of the complexity of his life that’s there before he moves on.

You enjoyed that sort of fantasy approach to that scene?

I thought that that was really important, and I thought it was beautifully written, because I did a lot of research about CTE and something that was really difficult about that was how it can only be diagnosed after death. I wanted to look at videos of people interacting with other people while having CTE, but that’s very hard because you have a lot of people who think they have it, or people who suspect that they might have it, and they seem like very normal people.

But then the rough thing is that when you are put under tension or conflict, stuff starts to surface. What that said to me is how terrifying it must be to feel this perpetual sense of unease and have no idea why. Because, again, it can’t get diagnosed. It doesn’t get exposed in an MRI. You just feel weird. And your decision making is just so wild. So the idea to get some sense of complete clarity, whether or not it’d be in a dream sequence, and know how it feels to have a neurotypical brain for even a couple moments before you go, I found the concept of that really interesting. I’m glad we were able to put that in.

It does make for a nice moment of closure. What was that for you? What was the last scene you shot as Aaron?

I remember the last thing I shot was actually laying on the ground, dead. That was probably on purpose. I mean, this might sound cold, but it was kind of nice. I just pretended to be dead. It was pretty easy. But before we shot that, it was pretty much back to back to back, like sad and dark and tragic. It really was a very, very intense sprint to the finish, and not something that I’ve had to do before.

Was it hard, then, letting Aaron go?

I don’t know. I like to say no because I don’t really subscribe to the idea that you have to take things home with you. I tried really hard in between takes to just be jovial and make jokes and stuff like that. Every so often, I would get stressed. But it never felt like Aaron is still with me. I don’t really believe in that. I think people have a lot of things to say about method actors but that’s not something that I do.

But I did not speak to anybody for like a month and a half after. So there’s that, too. Maybe there were certain parts of it that I needed to shake off a little bit. But largely, I try really hard to keep work at work.

On that note, is there something you’re taking away from this project, either personally or professionally?

Well, I didn’t think I could do something like this. I feel more capable than I did before I did this project, which is a cool feeling. But I’m finding out a lot of stuff about my response to both praise and criticism, which has been interesting. I get so uncomfortable with praise. It’s really weird. I don’t know. I was with a friend of mine, and we’ve known each other for a while, and she was telling me how good one of the episodes were. And I was like, “I need you to bookend that with an insult” — I don’t know. It’s a funny little thing of mine that I’m discovering.

A lot of it had to do with watching the show again and being like, I could do better. I would do this differently. It’s a frustrating feeling. But it’s also kind of nice. I like feeling that I have a lot of room to grow. I still very much feel like a newcomer. And it’s a cool feeling to be like, “Oh, this is a good place to start.” It gets me really excited for other stuff that I might do in the future.

Which begs the question: What is next?

I’m working on something that’s very, very early in development right now. Hopefully we’re going to get to writing at the top of next year. I’ve also just been very inspired to write. I got together with a friend of mine, and we’re working on a pilot for a comedy series. It’s just very exciting, because I’ve always wanted to write. I got really addicted to this sense of ownership over my creativity while I was doing this project. So yeah, there’s a couple things. Hopefully I can be a little bit more specific soon, but I am really excited about it all.

That does sound very exciting. And a nice change of pace, especially with a comedy.

Yes, truly. I’m not always crying and dying, I promise.

[ad_2]

Source link