Ocean Vuong’s magnificent and melancholy second novel, “The Emperor of Gladness,” is both ode and reproach. It pays tribute to the human ability to act with kindness toward others even when filled with hopelessness. Yet despair shrouds Vuong’s characters, immigrants and other outsiders for whom the American Dream isn’t an inkling. They form a protective community — a “circumstantial family,” as Vuong has referred to them — in which they converge as low-paid workers at a restaurant chain specializing in chicken and a corn bread recipe that produces “golden, palm sized mounds crusted with sugar.” Together, they selflessly work to keep each other from sinking further into despondency, substance abuse, and places where “the ghosts never leave.”

Protagonist Hai is the latest addition to their team. He is a Vietnamese refugee whose mother and grandmother brought him to the fictional town of East Gladness, Conn., in the wake of the Vietnam War and the destruction it wrought. The town they grow roots in is ironically named; from the omniscient narrator’s vantage point, New England’s beauty is in stark contrast to the community’s poverty and desperation. When we first encounter Hai, “in the midnight of his childhood and a lifetime from first light,” he perches atop the King Philip’s Bridge, being pelted by rain, “as black water churned like chemically softened granite below.” We come to find he is just out of rehab but hasn’t kicked his addiction to whatever drug he can buy or steal — his sole refuge from inescapable depression. We don’t initially know why he swings one leg over the rail and decides to jump, but he is saved from that act by a voice shouting from the riverbank: “Come back. Come back now! Jesus Mother Mary, not now, not today.”

The 82-year-old Lithuanian woman who talks Hai down from the ledge is Grazina, who’s lived alone in a ramshackle house by the water since her husband’s death, amid worsening bouts of dementia. She invites Hai in, urging him to “Go on, sit. You look like a dunked cookie.” He has nowhere to go since lying to his mother, pretending he’s been admitted to medical school in Boston, though he’s never graduated college. Grazina takes him in, and he proceeds to care for her as he would the beloved grandmother he’s recently lost.

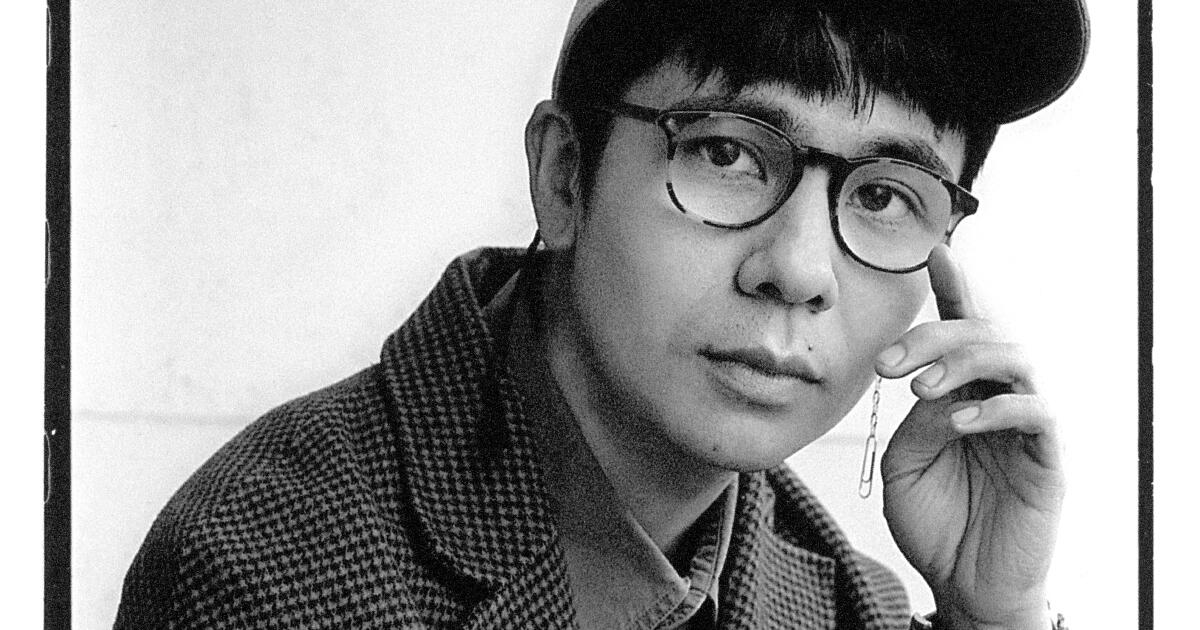

Through his cousin Sony, who resides in a nearby halfway house and obsesses about the Civil War, Hai is hired by Home Market, where he scrubs counters and toilets and works the cash register. Like his colleagues, he’s paid peanuts, but the crew — led by brawny amateur wrestler B.J. and her number two, barbecue expert Wayne — forge a close-knit bond that never flags, even when sacrifice is involved. Vuong, who worked in a string of fast-food restaurants and picked tobacco before receiving a MacArthur grant, vividly evokes the camaraderie he experienced, as well as the sights and sounds he absorbed: “Mingling with the processed food and personal hygiene products,” he writes, “was the garlicky, tar-ish and vinegar scent of human work.”

None of the down-on-their-luck players in Vuong’s repertoire experience reversals of fortune: There are no “improvement arcs” that elevate them out of their situations. As with most people in real life, their stories are not about profound change, but about keeping their heads above water. This poses a daunting challenge for a novelist, whose storylines so often depend on sudden tragedy, luck, or enlightenment, but Vuong, like Hai born in Vietnam and raised in Connecticut, meets the moment. He revels in his characters’ pluck and occasional heroism. Their expectations may have been tempered — if not extinguished — by reality, but they inhabit the world with quiet wisdom, and a sense of humor, as when Sony picks up a “sickly green slice of something” and asks “What’s a hare-loom tomato?” BJ peers over his shoulder and retorts: “It’s when rich people think f—-up looking things are more special than normal stuff.” This is not a joy ride of a novel, though there are many moments of joy.

Its opening pages are as melodic as a symphony, albeit one that exhorts the beauty of a Citgo gas station and the scrappy God First Beauty Salon, then juxtaposes descriptions of how autumn dissolves into winter: “As maples, poplars, and sassafras sway, the light filters amber through their leaving leaves. Even the steeple of the boarded-up Lutheran church grows from dove-white to day-old butter by noon.” There are hundreds of such passages throughout this 400-page book, which elevates the most prosaic of details, into hymn.

Vuong is a lauded poet whose paragraphs are shot through with sentences that enthrall and often land with a philosopher’s wisdom and economy. Take the first line: “The hardest thing in the world is to live only once.” How can such an observation be topped? And yet this is a novel that percolates and simmers, provoking questions about the reader’s privilege while prompting awe at the writer’s singular empathy — and his subjects’ humility. In writing this book, Vuong may have joined the ranks of an elite few great novelists, but his perspective remains rooted in that Connecticut town where he got his start.

Haber is a writer, editor and publishing strategist. She was director of Oprah’s Book Club and books editor for O, the Oprah Magazine.