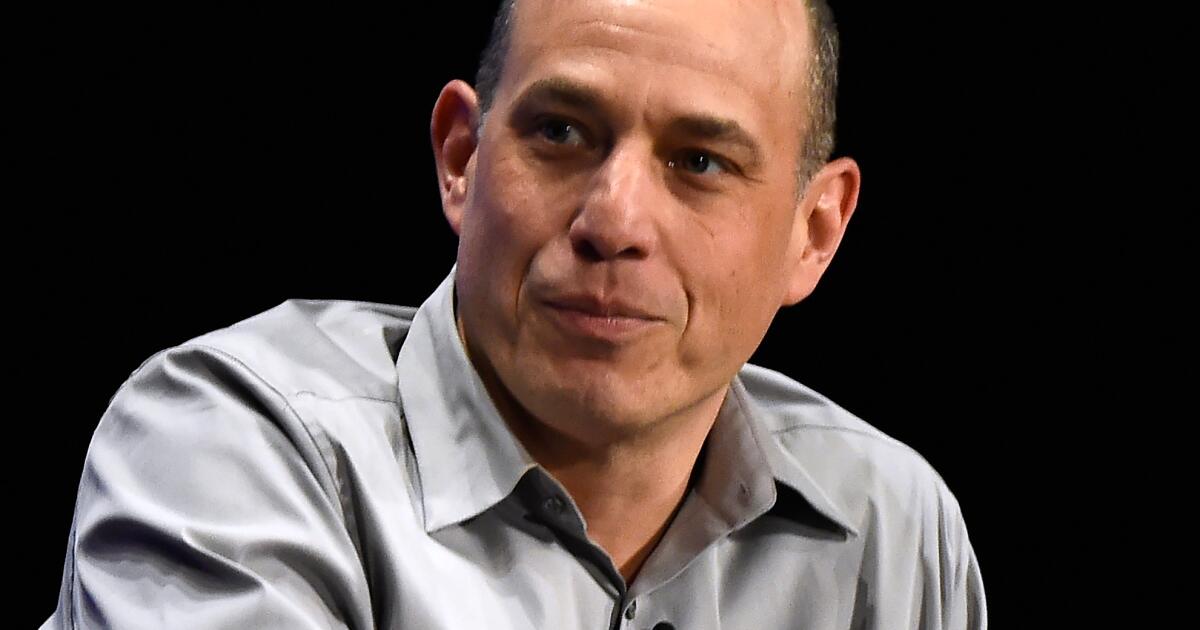

Bruce Eric Kaplan started a journal mid-pandemic, hoping to make sense of a world jolted by the vapor trails of Donald Trump’s presidency and COVID-19. The external chaos was leaking into his personal life, manifesting itself into a series of indignities that did little to quell his anxiety about a country turned upside down. The longtime cartoonist for the New Yorker and TV writer-producer was also engaged in another kind of madness: trying to set up his own passion project, a small-screen show about a May-December romance.

“I am looking to have a profound experience,” the veteran of “Girls,” “Six Feet Under” and “Seinfeld,” among other shows, writes in the first entry of his diary.

Spoiler alert: It doesn’t happen.

But Kaplan has turned the diary begun in early 2022 into a book. “They Went Another Way” is a funny, melancholy and poignant journal of Kaplan’s personal plague year.

“I basically started this journal to keep from going mad,” he says over coffee and bagels at the Clark Street Diner in Hollywood. “After I finished the book, I read Elizabeth Gilbert’s ‘Big Magic,’ which is basically telling the reader to listen to the world and whatever it tells you, write it down. That was my process.”

Kaplan didn’t like what the world was telling him: While committed to TV writing, he was trying to fend off the creeping cynicism about his ability to create meaningful work in Hollywood. By that point, the TV veteran had been unemployed for more than six months, and his children’s private school tuitions were looming over him like the sword of Damocles.

But existential despair doesn’t pay the bills, so he soldiers on with his project. Kaplan’s early diary entries are hopeful: His agents send his pilot to Glenn Close, whose reps tell his reps that she has read it and wants to do it. Kaplan finds a glimmer of optimism in an uncertain time: an A-list actor who wants to make his show.

But Hollywood is a place where hope frequently comes to die, and “They Went Another Way” is a comic primer on how good ideas are slowly strangled by an unwieldy and inefficient streamocracy whose lingua franca is the artfully evasive lie.

Things start off promisingly, as all first acts do. Close, Kaplan and “Palm Springs” director Max Barbakow meet on a Zoom call; she gushes about Kaplan’s script, they discuss potential co-stars and possible locations for the production. Kaplan’s agents create a submissions list of ideal buyers. While this project is slowly gestating, two prominent showrunners float Kaplan’s name as a supervising producer for their new show. It’s all kinda, sorta happening, but Kaplan is struggling with writer’s block and a busted heating unit, among other disturbances both domestic and global.

Thus begins Kaplan’s mad scramble for sanity, as the TV writer tries to plug the leaky vessel that is his life, which he chronicles in cringey detail in his book. “I was at a crossroads at that point,” Kaplan says now. “My wife and I were also trying to figure out if we wanted to move to New York with our kids in the middle of all of this. I just felt like, ‘This is what I’m supposed to write about, the stuff that is actually happening to me.’”

It doesn’t take long for the initial blast of heat to cool on Kaplan’s project. Soon, he finds himself in an all too familiar position for anyone trying to get anything done in Hollywood. “I am waiting to hear if Max Barbakow is officially in for the Glenn Close script,” Kaplan writes. “I am waiting to hear when I am going to meet with Will Forte about my New Zealand show. And I am actually waiting on several other things I don’t feel like typing about.”

Kaplan is drawn into a vortex of elongated time, where a day turns into a week turns into a month and where deadlines are written on water. Close emails Kaplan about contacting Pete Davidson as her co-star; per Kaplan, she has “great chemistry with” the “Saturday Night Live” alum, a friend of hers. Close texts a copy of the script to Davidson, who reads the first 11 pages and wants to do it, which, Kaplan writes, “is quite something, since his character doesn’t even show up until pages after that.”

The process of getting everyone on the same Zoom call becomes needlessly complex and Kafkaesque. Davidson repeatedly calls in sick, when in fact simple Google searches reveal that he is out of the country with his girlfriend Kim Kardashian, or some such. Then when it seems as if momentum might be turning in Kaplan’s direction, there is a demand for more — more story, more plot, more writing for free. Hope is always crashing against the shoals of disappointment. Showtime wants to make Kaplan’s show, then Netflix appears to be in “first position.” Then both go away.

This push and pull, of taking one step forward then one step back, leaves Kaplan spiritually spent. He fends off anxiety by meditating, exercising and obsessively cleaning his house. He almost loses his mind trying to complete his daughter’s private school application, and he and his wife are both injured by stray soccer balls in separate events at his daughter’s team practice. He ponders alternate careers. “My escape plan is…to bring turkey sandwiches to New Zealand,” Kaplan writes. “I will get some turkeys shipped there and have a turkey farm…if this script doesn’t sell, then I am definitely going to explore becoming a turkey farmer in New Zealand.”

There is no such thing as a sure thing, but the streaming cosmos has given that truism a power boost; there are so many potential projects spread across so many creators that it seems as if no one can commit to anything, let alone focus on any one thing, for very long, which has been made even worse by the severe retrenchment among Hollywood studios to greenlight any new projects. Risk aversion has become an end in itself. Kaplan, who began his career in the four network era, has seen the changes firsthand.

“When there were four networks, my agent would set up pitches, and you would have a meeting within 48 hours of that initial call,” says Kaplan. “Within a day, you would know whether they wanted it or not. The executives would ask about the idea and the characters. That was it. They wouldn’t ask what the first season finale was going to be or ask you to lay out the second season.”

When Kaplan, against his better instincts, does agree to write a second script for one potential buyer, it doesn’t go well. Close rejects the script outright, telling Kaplan, “If I don’t find it interesting, then I assume everyone will find it uninteresting.” This prompts Kaplan to wonder in his journal whether “thinking everyone would have the same feeling as you do possibly indicated.”

Suffice it to say, everything eventually dissolves into the ether: Close goes away, as do all of Kaplan’s other projects. The end of the year finds Kaplan him in the same place as he was in January, but not without having endured a flurry of Zoom calls, emails and texts that leave him depleted. Still, he wills himself to begin anew. It’s all he knows how to do.

“This is my reality.” he says, “and I’m just trying to make the best of it.”