The summer of 1977, when I was sixteen years old, I started work at Andy Warhol’s Factory.

I was a teen stalker, a fantasist who mostly preferred sitting on a stoop opposite someone’s house, noting the street-scene in my diary, to actually meeting the person inside, and Andy had long been one of my simmering obsessions.

My parents – New York society people with an interest in downtown art – had first met Andy in the late fifties, when my father was working as a fashion photographer and Andy was still an illustrator dressing windows for Bonwit Teller. My father liked to say that back then he’d thought Andy Warhol an embarrassing little creep whose determination to be famous was clearly doomed. But my mother had a taste for oddball dreamers and she and Andy became friends; she appeared in one of his 1964 Screen Tests. I’d been raised on her stories of the Factory – the silver-tinfoil-walled spaceship where Andy, pedaling on his exercise bike, swigged codeine-infused cough syrup and watched his superstars squabble and self-destruct. Watched and subtly egged them on. At a certain point, my mother got spooked by how many of his beautiful, lost young creatures ended up dead.

In 1968, Andy was shot by Valerie Solanas and he too, briefly, died. It was a time when America’s chickens, in Malcolm X’s phrase, seemed to be coming home to roost – Andy’s shooting was edged off the front pages by Robert F. Kennedy’s two days later – and when Andy came back from the dead, with his insides shattered and sewn together again, he was seemingly cured of his taste for watching other people detonate.

On 7 December 1976, I finally succeeded in pestering my parents into introducing me to Andy Warhol.

By then, they had devolved into merely social, semi-professional friends who exchanged poinsettia plants at Christmas, and the Andy I had wanted to know – the ghostly cyclist who could mesmerize you for eight hours with a flickery image of a skyscraper – had been supplanted by the art-businessman flanked by pinstripe-suited managers. And I too was in a different phase. By the time I actually made it to the Factory, I was less interested in Andy than in dancing at Studio 54 with his managers.

Our first meeting was at La Grenouille, a fancy French restaurant in Midtown. My parents had invited Andy to dinner, and later that night, I wrote my first impression of him in my diary. Andy was ‘standing there in his dinner jacket and blue jeans, tape recorder tucked under his arm, looking shy and uncertain but friendly’. He had brought as his date Bianca Jagger, gorgeous in a purple fox stole and a gold lamé toque. They ordered oysters and a spinach soufflé, which she sent back because, as she explained to the waiter, it was affreux. ‘Halfway through dinner Mummy asked me to switch places with her so I could talk to Andy. Andy said something about my mother being “mean” not to let me sit next to him before. So we talked the rest of the evening. I was a little shy and ended up feeling oddly depressed and dispirited, sort of drained. He said I looked like a movie star, had I ever thought of being one. That seemed like the sort of thing he says to about five hundred people a week . . . He asked me to bring down my whole class to the studio – that too I found depressing. I asked “Why don’t you come to Brearley [the private girls’ school where I was in eleventh grade]?” He said no, he could never do that, something about being too shy. I said, “Well, a lot of them are really awful.” He said, “Well, bring the awful ones too.” He’s very easy to talk to, I kept saying things I wished I hadn’t.’

My mother had told Andy I was a writer and he asked if there was anyone I wanted to write about for his magazine Interview.

He said they needed something for the January issue. ‘“We want someone young and really new – what have you seen on Broadway, who can you think of” on and on, I was completely stuck. Ludicrously I suggested Mr [Edward] Gorey. Andy said, “Oh come on. He’s creepy – he’s really old. I saw him walking along Park Avenue the other day. He’s too peculiar for me.” That made me laugh. “Too peculiar for you? He’s just a bit moldy. I was obsessed with him for about two years.” Mr Gorey’s star was pretty dim that night.’

I suggested other writers, photographers, film-makers whose work I admired. All too old, too peculiar. Finally, I proposed the choreographer Andy de Groat, who had just collaborated on Philip Glass and Robert Wilson’s Einstein on the Beach.

Andy agreed, ‘though he thought Einstein on the Beach was “stinky”. He wanted some more people. I told him I’d provide some later. Andy said to call A de G tomorrow, and then him. “The piece has to be in really soon.”’

Andy’s description of the evening, published in his Diaries, accords with mine, but he added a nice coda. ‘The Eberstadt daughter didn’t say anything during dinner but then she finally blurted out that she used to go to Union Square and stare up at the Factory, so that was thrilling to hear from this beautiful girl. I told her she should come down and do interviews for Interview and she said, “Good! I need the money.” Isn’t that a great line? I mean, here Freddy’s father died and left him a whole stock brokerage company.’

As a kid, I used to feel this need to be outside in the dark, looking up at lighted windows, imagining the life inside. I still do. But nowadays the lighted window is my own, my husband and children are inside, but something broken and uncured keeps me outside, sniffing the night wind and rain, unable to join the circle by the fire.

The Andy I was drawn to was dogged by this same self-imposed and unassuageable loneliness, though his version of the family fire was the VIP lounge at Studio 54 with Truman Capote, Halston and Liza Minnelli. Yet no matter how famous he became, he was still the ‘embarrassing little creep’ who, when he first arrived in New York, had harassed Truman Capote with daily fan letters, phone calls, and camped out on his doorstep; he was still the balding twenty-something sitting every day at the counter of Chock full o’Nuts, eating the same cream-cheese sandwich on date-nut bread; someone who founded his art on boredom, repetition, because only unvarying sameness could soothe his raging anxiety.

I told Andy the first time we met that this was something we had in common – that although, as he put it in his Diaries, I was a ‘beautiful girl’, a banker’s granddaughter, I was also a freak like him, a person who in some way would rather stand outside staring up at the Factory windows than be invited in.

Even today, it’s this same dividedness in Andy that gives me a pang of fellow feeling, the same compulsion to hide away that overrules your hunger to belong, a compulsion that then leaves you feeling too lonely, too weird, too left out of everyone else’s fun. And why does the loneliness feel truer, more essential than any love or acclaim?

By mid-December, I was heading down to Union Square every day after school to transcribe my tape-recorded interview with Andy de Groat. I would install myself at the front desk of Andy Warhol Enterprises, play back a couple of sentences, and type them up two-fingered, dragging out the process tortoise-slow. My pretext was that I didn’t have a working typewriter at home, but in truth the Factory had become my happy place.

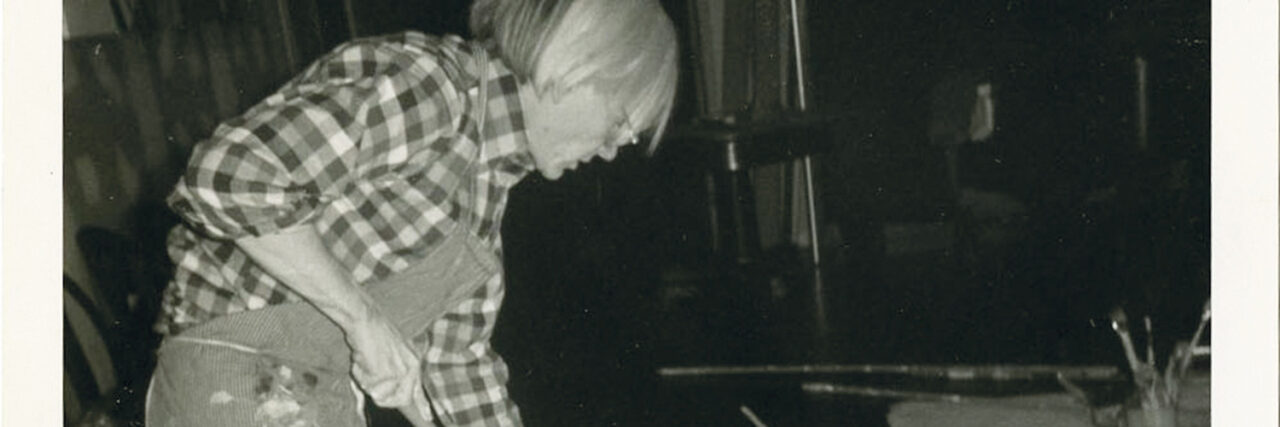

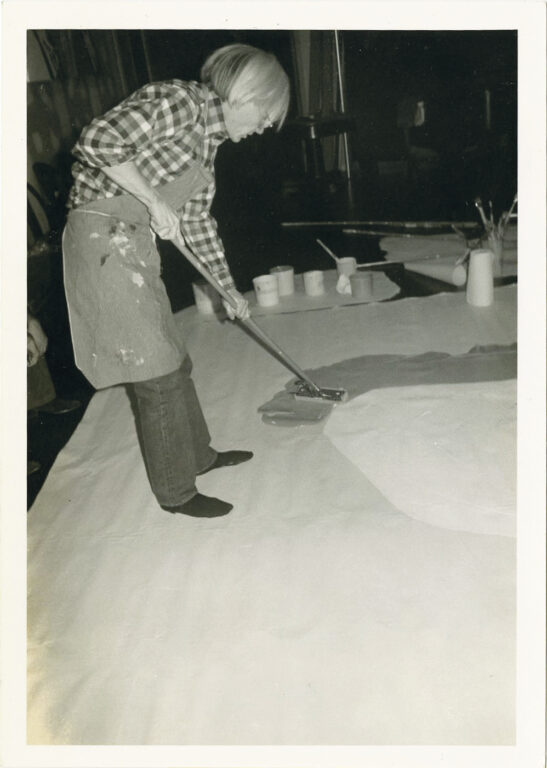

My favorite moment was at the end of the day when Andy put on his apron, picked up a broom, and swept the floor clean – I liked the monastic discipline, the humility of the act. If I got lucky, I would then share a ride uptown with either him or his business manager Fred Hughes, the enigmatic Texan dandy who was the one I actually had a crush on.

One night, Andy and I were sitting in the back of a yellow cab hurtling through the sooty entrails of the Pan Am Building and out onto Park Avenue.

We were discussing our evening plans – in my case, studying for a Russian history test with my friend Martine; in Andy’s case, a dinner party given by Fereydoun Hoveyda, the Iranian Ambassador to the UN who had been the conduit for Andy’s portraits of the Shah and his family. (This was two years before the Revolution, which the ambassador survived, although his brother, the Prime Minister, was executed by firing squad.)

On these taxi rides, I became familiar with Andy’s conversational technique, how he negotiated his mix of shyness, curiosity, malice. He was a persistent questioner, and what he wanted to hear was the most shameful thing about whomever it was we both knew, and because I wanted to please him, I inevitably divulged some incriminating tidbit and his reaction was always, ‘Oh come on. Really???’

I was used to this kind of inquisition from my mother, though she never feigned disbelief, and as with her, I ended up cursing my inability to keep my mouth shut. Andy knew all about mother–child oversharing; his mother lived with him for years and coauthored his first art books, and my guess was that he inherited his malice from her, it was his mother tongue, although it coexisted with a certain vestigial innocence: a part of him that was stuck at an age between child and cat, that wanted to timidly lick the boy he loved all over.

6 January 1977.

I was home sick in bed; I was often sick in bed growing up.

Catherine Guinness, Andy’s assistant, phoned to discuss a photograph to go with the de Groat piece. They had decided that Robert Mapplethorpe should take the picture.

I asked after Andy.

‘Andy’s busy sweeping up cigarette butts.’ She put him on the phone.

I heard the mechanical-man voice with its campy singsong intonations, teasing, a little flirty, and my heart leapt.

AW: Gee, it’s really too bad you’re sick. How did you get it? Who have you been carrying on with?

Me: No one – it’s really disappointing.

AW: Well, are you typing and typing away?

Me: I’m in bed all day. My mother has to read aloud to me.

AW: Did you get nice presents for Christmas? Did you get what you wanted?

Me: Well, not really. Will you get me what I want for Christmas?

AW: Oh I meant to get you a Christmas present but I never got around to it.

Me: Yes, I was so jealous when you gave Mummy something and not me.

AW: Oh were you? Well, I’ll get you something. When are you coming to the Factory next? I’ll give you a present when I see you at the Factory.

I was a resourceful kid; all winter and spring, I produced a steady enough stream of interviews to keep me coming down to Union Square with pieces to transcribe. One day Chris Hemphill, the office assistant, had good news for me: their receptionist was going on maternity leave in June.

As soon as school let out, I started my summer job at Andy Warhol Enterprises. The mid to late 1970s marked a low point both in Andy’s reputation and his creative output, and in those days the Factory’s chief business seemed to be managing the Warhol brand: racking up corporate sponsorships; drumming up advertisements for Interview; above all, getting portraits commissioned. I too was inducted into the hustle – how many of my parents’ rich friends could I persuade to commission a silkscreen portrait? If I succeeded, I would get 25 percent of the price, which I noted as being $25,000. (‘Good! I need the money.’)

Despite the corporate veneer, the atmosphere at the Factory was one of slapstick merriment. That I answered the phone in an inaudible mumble and couldn’t switch from one call to another without cutting off both parties made me the dream receptionist. Andy, Fred, and Catherine all took turns imitating my telephone voice; callers wanted to know if I was still asleep in bed.

In a TV interview from the same period, a reporter accused Andy of being ‘commercial’.

‘I’m a commercial person,’ Andy conceded testily.

‘Why?’

He considered. ‘Well, got a lotta mouths to feed. Gotta bring home the bacon.’ His tone was curt, he was sick of this criticism, of never being taken as seriously as peers such as Robert Rauschenberg or Jasper Johns.

But his answer also reflected his image of himself as ‘Pop’ in the sense of someone who was running a mom-and-pop store with no mom to help out, a single father who needed to keep his feckless kids in line.

If he weren’t there with his apron and broom, we would drown in cigarette butts.

Every morning, I was supposed to be in by nine, in time to answer the phone when Andy called from home to check that all the slackers on his payroll were in the office.

Vincent? Fred? Ronnie? Chris? Everyone was present, though some were looking a little ragged: Ronnie Cutrone had got locked out of his apartment the night before and had to shack up with an ex-girlfriend; Fred Hughes had a black eye. ‘I got into a fight with someone who said Andy was queer,’ he told me, and I believed him; the next inquirers were told respectively, ‘Nenna [my nickname] hit me’, ‘Andy hit me’, and ‘It’s supposed to be punk – that’s a fad that’s so new not even Nenna knows about it’. In fact, Fred’s tendency to fall down stairs turned out to be an early sign of the multiple sclerosis that would kill him at fifty-seven.

Andy came in later, just in time to hide before the first guests arrived. Even on his own turf he was awkward, and gave the impression, I noted in my diary, ‘of hanging around people, rather than the other way around’.

At noon I used to go to Brownie’s, the health-food store around the corner, to pick up a stack of avocado and tuna sandwiches for lunch. There were always visiting rock stars, Hollywood directors, European princesses. A lotta mouths to feed. In the afternoons, Victor Hugo, Halston’s Venezuelan boyfriend, usually showed up with models he’d scouted in gay bars and baths. Andy and his assistants disappeared into the back of the Factory – an area that was tacitly out of bounds to me. This was where Andy made his ‘Landscapes’ – Polaroids of naked men posing and having sex that were then turned into prints and silkscreens.

There was an effort to keep me sheltered from the nude photo shoots, although the finished canvases were sometimes propped against my desk for Victor’s inspection, with much joking about ‘King Kong unclothed’. I looked elsewhere while they estimated cock size. How would I know and why would I care whether this particular specimen was XXL or XXXL?

After work, Andy and his crew, me included, went on to fashion shows, tennis matches, movie premieres, dinner parties, winding up at Studio 54 or Xenon. But even when I got home at 3 or 4 a.m., I still sat down and recorded the previous day in my diary.

All summer I was soaring on a wave of adrenaline, drugs, alcohol and teen hormones. But there were times when I crashed, needed to reassure myself that ‘this is just the trashy segment of a very real life’. At such moments, I found myself increasingly drawn to Andy, whose presence – in contrast to my mother’s experience of him ten years earlier – felt mild, steadying.

Towards the middle of July, something changed. There are holes in my diary – events so disturbing I could only allude to their aftermath. There was the weekend when I was supposedly staying with a school friend in Southampton, but I persuaded this really sleazy fashion designer to hire a speedboat and zip me out to Andy’s compound on Montauk – an escapade that was relayed back to my parents by a journalist.

When my parents and Andy next met – on board a chartered bus to a soccer match of the New York Cosmos, a team founded by Atlantic Records mogul Ahmet Ertegun and his brother Nesuhi – my father yelled at Andy. Andy accidentally called him ‘Mr Eberstadt’, and my parents realized then that some border had been crossed of who was friends with whom.

Was Andy really Pop, the boss who had a lotta mouths to feed, or was he a child still frightened of other people’s fathers?

I too had a scare. My father threatened to yank me from the Factory and only agreed to let me keep working there on condition that I was home every evening by 8 p.m. Though I wasn’t cured of my thrill-seeking, the curfew gave me a welcome breather.

And weirdly it was this blow-up, in which Andy had been humiliated and made to suffer for my misbehavior, that altered our relationship, deepening it into something more intimate, more fusional.

Our morning phone calls were now long-drawn; telephone-friendship was freer, unencumbered by the embarrassment of bodies. We slipped into a comfortable routine: as soon as I got into the office, after watering the plants, I dialed up astrologer Jeane Dixon to hear everybody’s horoscope, and when Andy phoned, I relayed his fortune for the day. Hello Leo, I intoned in Dixon’s rich cheery voice, and Andy feigned either excitement or alarm. Was an old rival really going to make trouble for him? That was so rotten! Who could that be? Was today really the right day for important financial decisions? Did that mean he should be asking for more money for the Toyota endorsement?

Andy told me what he’d been up to that morning: he was in his kitchen making marmalade. This particular batch was too runny, it hadn’t really jelled. He complained about his boyfriend Jed, whose mother and sister he found tacky. He hated the way Jed behaved when his family was around.

He asked about the boys I’d been seeing. Was Michael behaving himself? What about Fred? A sharp plaintive note entered his voice, the bite of jealousy, of feeling left out.

We floated in this disembodied, homey place, thick with orange rind. The intimacy depended on the illusion that I would always be there, although we both knew I was leaving in August.

My last week at the Factory, William Copley, an artist and collector who lived in a townhouse with a circular bar, a pinball machine, lots of Warhols, and twenty-odd stuffed sheep by the French furniture designers Les Lalanne, gave a dinner party. Andy got me invited, and I negotiated a no-curfew night with my father.

It was a complicated evening, a kind of Midsummer Night’s Dream in which most of the guests seemed to be unhappily chasing after someone who didn’t love them.

Halfway through the party, a cocaine dealer arrived, and Bob Colacello – editor of Interview – and Fred Hughes and I locked ourselves into the bathroom, and Andy, who didn’t do drugs, was left outside.

‘The next day, August 2nd, as soon as I got in, Vincent said, “Andy called and wants to speak to you,” but when Vincent called him back, Andy wouldn’t speak to me,’ I wrote in my diary. ‘Later Bob called to warn me that Andy had called him and screamed at him about last night. He told Bob he was a terrible person, the scum of the earth to have taken me to the bathroom – that the way we’d behaved was utterly unforgivable. When Andy called the Factory next, he wouldn’t even say hello to me but got put on to Catherine. I knew he was telling her about it, but when I tried to pump her afterwards she wouldn’t say . . . When Andy got in, he began yelling at Fred about the new issue of Interview and only after ages admitted that it was about last night he was mad. When no one was around and Andy was hanging around my desk, not looking at me, I finally said, “Andy, I hear you’re really mad at me.” His face was positively contorted with anger and embarrassment – he was blushing and twitching. “Yeah, I am mad – very mad. After the way your father bawled me out, it was terrible for you to behave the way you did. I’m trying to protect you and you went and did that. I’m really disappointed in you.”

When I talked to Bob later, he said that what Andy had really got mad about was not the coke which he is scared of and blows out of all proportion, but that he said that he had asked me to that party and I was his date but I hadn’t spoken to him at all.

Fred Hughes and I were planning to go out to lunch but it didn’t seem tactful so we just ordered sardine sandwiches from Jason’s and took them to the park in Union Square to eat. After that, we looked at some antique stores and Fred showed me an enormous birchwood Adirondack sofa he was getting for Andy’s birthday, and I bought Mummy some green Bakelite Art Deco jewelry to wear with a dress of hers . . . Andy really liked it but when I gave it to Mummy she thought I must have done something really awful.’

It’s odd. The year I worked at the Factory felt like the happiest and most exciting period of my life, a whirl of discos, parties, famous people. Yet afterwards, when I looked back, it seemed a dangerously empty, soul-destroying time, and today what pierces my heart is the morning Andy stood by my desk, blushing, face contorted, too angry and hurt to speak.

Rereading my teen diaries, I have the impression of someone driving a car repeatedly over a cliff, seeing how often they can walk away alive. There weren’t many adults who were looking out for me, but Andy felt like one of them. ‘I’m trying to protect you,’ he said. It was true; he was. And he trusted me enough to tell me that I’d hurt his feelings . . .

My last day at the Factory, we invited my mother to a farewell lunch, and in the afternoon I got paid my summer’s wages. I’d been given the choice between being paid in cash or in art, and I’d chosen art.

Ronnie had laid out stacks of silkscreens across the wooden floor. It was like picking a puppy from a litter, a carpet from an Ottoman caravanseray. I pored through sheaves of flaming macaw-colored Elizabeth Taylors and Mick Jaggers and Chairman Maos, and opted for dictatorship over entertainment.

When I’d chosen two Mao silkscreens – one blue-black and ochre-brown, the other turquoise and Astroturf-green – Andy scribbled over them in Magic Marker. He added two pink-and-purple prints of cows, and scrawled on the front of all four, ‘To Nenna, with love Andy.’

Fred was watching. ‘Andy never dedicates them on the front.’ He sounded put out, as if I were getting away with more than I should.

I gave Andy a big kiss. ‘Oh gee,’ he said, startled. ‘You just gave me a French kiss. Did Fred teach you how to do that?’

‘I’m going to miss you,’ I said.

He looked surprised. ‘Aren’t you coming back to work for us in the fall?’

I said of course I was but I didn’t, I never really came back. In September, I brought Andy, Fred, Bob and Catherine to lunch in my school cafeteria, and after that we still met up occasionally, but it wasn’t the same. We were no longer floating in the marmalade fug of the morning phone call, we no longer knew each other’s horoscope or what parties we’d each been to the night before.

The next year, 1978, I went to England to study for the entrance exams that would get me into Oxford. It was a conflicted move: I was desperate to escape my parents’ world, the glittery, over-sophisticated, fame-studded New York in which I’d grown up; I felt as if my survival depended on it. But I also wanted to take my Manhattan glamor with me.

My final year at Oxford, I brought one of the two Mao silkscreens to hang on the wall of my undergraduate room. But some Oedipal impulse intervened, an urge to murder my elders: going off to find a picture hook, I left the Mao propped against an electric heater and it caught fire.

I never got the picture restored; in my arrogance, I felt as if its scorch marks were as integral a part of the Mao’s history as its ‘To Nenna with love’.

In 1987, I was back in New York when I heard that Andy had died after a routine gallbladder operation. I was flooded by a raw grief that even today I can’t begin to process. I hadn’t seen him for a couple of years: we had each entered different phases of our lives. Andy had been taken up by younger artists like Basquiat and Keith Haring and had gone back to painting, and I was going through a puritanical reaction against my wild teens, but I’d nonetheless counted on a future where we would reconverge.

At his memorial in St Patrick’s Cathedral, the art historian John Richardson gave a eulogy about the intensely lived spirituality that suffused Andy’s art, and it seemed like a turning point in how his work would be viewed, a recognition of the religious faith mixed in with the cynicism.

It’s now almost half a century since my summer at the Factory. All these decades, I’ve only allowed myself to think about Andy through a kind of dissociation, focusing on him not as someone I actually knew, the boss who was sometimes mean and petty, sometimes cozy, vulnerable, loving, but as a historical figure, a prophet of contemporary America and its fame-and-death-and-money machines.

The burnt Mao hangs on my wall: its midnight-blue face is haloed in black smoke and shards of its crinkled flesh have got stuck to the Perspex frame. The damage from that long-ago electrical fire has turned the Mao into what the French after the First World War called a mutilé de guerre, it’s a cultic sacrifice, like a Madonna that bleeds tears.

When I look at the Mao’s charred flesh, I think of Andy’s own stigmata, the molten lacerations of his acne-devoured face, the purple-and-white sutures from the shooting that kept his guts from spilling out, and I can feel the daily mortification, the pain of inhabiting his body.

I’m picturing Andy at the end of the day with his apron and broom; he’s a tightwad who is teaching his employees a lesson about hard work, but there is an expression on his face of sweetness, humility, resignation, and suddenly I want to kiss him. Oh gee, he says, you just gave me a French kiss.

Photograph by Bob Colacello, Andy at the Factory, 860 Broadway, New York, c. 1976

Courtesy of the artist and Vito Schnabel Gallery